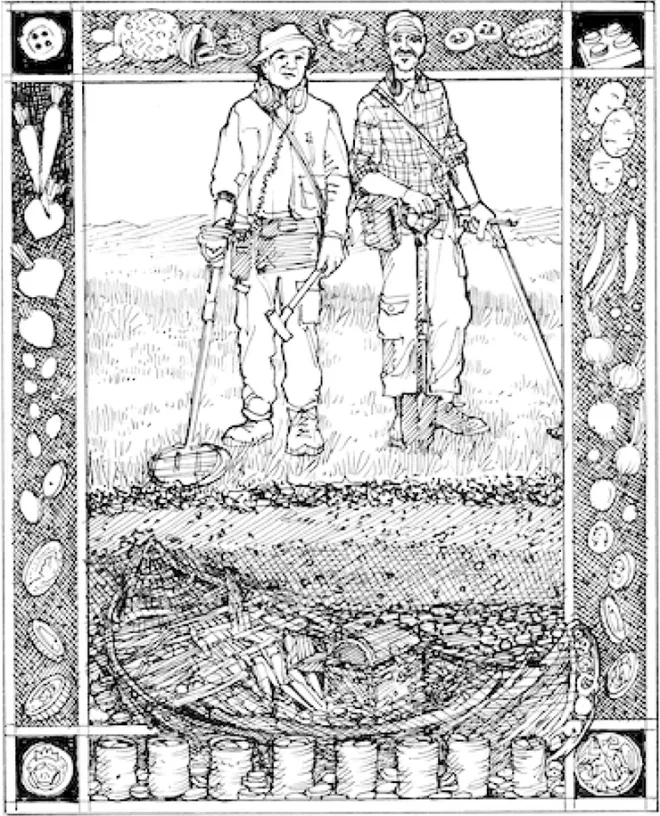

Is anybody—other than me, that is—a fan of the BBC series “Dectorists”? The show centers around the adventures of Lance and Andy (Toby Jones and Mackenzie Crook) of Britain’s (wholly imaginary) Danebury Metal Detecting Club. The club members, armed with metal detectors, obsessively comb the landscape searching for treasure, which they almost never find. They do, however, turn up a lot of bottle caps and buttons, and during the credits at the end of every episode there’s a fleeting view of the incredible possibilities: a below-earth scan of a treasure-laden Anglo-Saxon ship buried practically beneath Lance and Andy’s feet. It’s a great series with a satisfying ending about which I’m not going to tell you. (It’s complicated.) But it involves gold.

Who doesn’t dream of finding buried treasure?

And people do periodically find it, just while digging in their gardens.

Just this past year, gardeners in Hampshire in southern England—spading up soil for planting season—found a hoard of medieval gold and silver coins. The coins were dated to the late 15th and early 16th centuries and spanned the reigns of five British kings: Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III, Henry VII, and Henry VIII. Most of the coins were gold angels—so-called because on one side they feature a picture of the Archangel Michael killing a (smallish) dragon. There were four particularly rare Tudor coins in the stash, which promptly made the news: gold crowns variously bearing the initials of Henry VIII’s first three wives—Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, and Jane Seymour—along with the signature Tudor rose. (No coins were ever dedicated to Henry’s last three wives; perhaps by then the royal mint had despaired of keeping pace with his rate of marital turnover.) The coins, at the time they were buried—sometime around 1540—would have been worth about $18,000 in modern money, then a fortune.

One guess, by coin expert John Naylor from the Ashmolean Museum, is that the hoard was buried by a clergyman in the wake of Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. Henry, who abandoned the Roman Catholic Church in 1534 in order to marry Anne Boleyn, ordered all English monasteries disbanded, with their lands and wealth reverting to the Crown—that is, going straight into Henry’s perennially empty pockets. It’s not a bad assumption that perhaps the Hampshire coins were buried to keep them out of the paws of the rapacious king.

Other finds have been even more impressive. In 2012, a gardener in Ackworth, England unearthed a pottery jar containing nearly 600 gold coins and a gold ring inscribed with the phrase “When this you see, remember me.” The hoard was dated to the time of the English Civil War, a mid-17th-century clash between the supporters of the king (the Cavaliers) and the Puritan backers of Oliver Cromwell (the Roundheads)—a fraught period during which the cautious might well have buried their savings for safekeeping.

In 2004, Ken Allen of Thornbury, in the process of digging a pond in his backyard garden, found a cache of 11,450 Roman coins dating to the third century; and in 2020, a birdwatcher, tramping through a farmer’s field while tracking a pair of magpies, kicked up a Celtic gold coin. He dashed home for his metal detector and soon found a copper pot crammed with 1300 gold staters dating to 40-50 CE, when the redheaded Queen Boudica was battling the invading Romans. The editors of Treasure Hunting magazine—yes, there’s an entire magazine devoted to treasure hunting—suggest that the hoard may have been a war chest, intended to help fund Boudica’s military campaigns.

American gardeners aren’t likely to strike it rich on Celtic staters or Tudor gold crowns, but our situation isn’t hopeless. Treasure happens even here. In 2014, a Northern California couple unearthed eight tin cans in their backyard, each packed with mint-condition 19th century gold coins—valued today at a grand total of $10 million.

So let’s say you happen upon a pot—or eight cans—of gold while you’re crawling around in your vegetable plot planting turnips. Can you keep it?

It’s a question that has bedeviled treasure hunters since at least the time of the Romans. It turns out that Romans, by law, could keep half of any discovered treasure: that is, if you, a Roman citizen, stumbled upon a crate of silver ingots while prowling about the Coliseum, half went to you and the other half to the emperor.

Today it’s a bit more complicated. In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the Treasure Act of 1996 defines “treasure” as anything made of gold or silver that’s more than 300 years old. Anything that meets that definition by law belongs to the Crown—though the Crown, to foster good relationships with treasure hunters and archaeologists, routinely pays finders the full market value of their discoveries. (This isn’t a perfect system: a bronze Roman parade helmet, dug up in Cumbria in 2010, didn’t meet the legal definition of treasure, and so—to the dismay of scientists and museums—was auctioned off to a private collector.)

In the United States, treasure hunting—provided you don’t do it on federal property, which is a felony and can land you in jail—is pretty much a matter of finders-keepers. Laws vary a bit from state to state, but generally speaking, if you find a chest of doubloons in your tomato patch, it’s all yours. (If it’s a rental tomato patch, it’s just half yours—you have to split it with the property owner.)

So far our garden has been a bust for buried treasure. I’ve been digging in it for years, and the most exciting finds to date have been a lot of rocks, a piece of a teacup, and a couple of Lego bricks (Lance and Andy would sympathize)—though there’s a lot to be said for our annual harvest of carrots, potatoes, onions, and beets. After all, people need vegetables. Robinson Crusoe, stranded on his desert island with a parcel of gold and silver retrieved from his wrecked ship, said that he would gladly have traded the whole thing for a handful of peas and beans (and a bottle of ink). It’s important to keep our priorities straight. Treasure is as treasure does. After all, you can’t eat doubloons.

Still, I can’t help hoping.

It’s known for a fact that Samuel de Champlain passed by our way in 1609 with a flotilla of 24 canoes. Wouldn’t you think some long-ago French explorer might—just possibly—have left behind a little bag of gold? ❖