My father’s garden was beautifully kept, immaculately mowed and weeded—except for one corner that was totally fenced off so neither people or creatures (he had hens running free and several cats) could get in. It was, he told me, “for the fairies.”

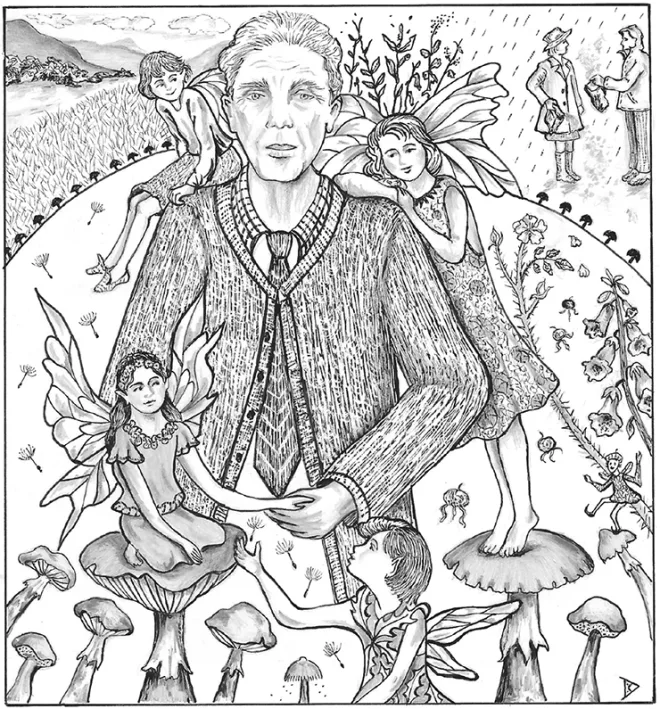

Daddy did not look like the stereotyped believer in fairies: he was very gentlemanly and, indeed, I never saw him without a tie. He was honest almost to a fault: I even remember him leaving a note on the windshield of a car after he accidentally nicked its paint! He was, however, a theosophist and a Scotsman.

Theosophy, popularized in the early 20th century by a Russian lady, Madam Blavatsky, included an interest in astral spirits and a strong belief in the existence and accessibility of fairies, which is still part of their creed today. I do not think my father ever saw a fairy, although I know he would have liked to, but it did not stop him believing in them.

Although he later lived in England, my father came from Scotland, a land with a long tradition of “second sight” and the mystical powers of natural spirits. The Highlands of Scotland are an easy place to believe in fairies. Its misty climate and secret gullies, groves, and streams suggest magic everywhere. A Scottish clergyman, Robert Kirk, wrote The Secret Commonwealth in 1691 and—as the seventh son in his family—claimed to be an authority on fairies. He wrote that Scots-men with second sight who moved to America “quite lose this Qualitie.” Settlers to the New World were likely more interested in farming the wilderness than thinking about fairies. Their iron plows and later the expansion of settlement with new railways were not hindered by any concern for little people.

Fairies were known to fear iron in particular. Sometimes an iron bar was put into a cradle to protect the baby from being stolen by the fairies and substituted with a “changeling” or fairy baby. If a human baby was disfigured or had other problems, it was often assumed (comfortingly) that it was a changeling.

In Ireland, as in Scotland, there is a long tradition of fairies. These were not small pretty creatures dancing through the flowers. They could be the size of humans, and often of terrifying appearance, like the dreaded Daoine Sidhe, who were known to kidnap young women. In cultures wholly dependent on the vagaries of nature, where things could go well or inexplicably disastrously, fairies could be held responsible because they were a more intimate way of explaining personal events than the vague machinations of a detached universal power. After all, they can live in the garden and know our lives. They can be appeased with saucers of milk, or food, or places to shelter.

Historically fairies were not the tiny winged creatures we envision today. In Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Titania and Oberon are the size of humans, and they have no wings. Shakespeare’s Ariel and Puck can change shape, but they are not winged. Ariel tells us that “on the bat’s back I do fly.”

Robert Kirk described fairies as “betwixt man and angels.” They have no souls, and although they live longer than humans, they do eventually die. Fairies live in a different “element” from humans and reveal themselves only to those with “second sight”—rather as we can reveal ourselves to fishes when we dive into their element in “the Bottom of the seas.” Fairies are, he wrote, “somewhat of the nature of a condensed cloud,” and their “camaelion-lyke Bodies swim in the air near the earth.”

In 1712, Alexander Pope wrote The Rape of the Lock, which is rich in information about fairies. The poem describes a young woman whose admirer steals a lock of her hair, and how the Sylphs, or fairies protecting her, try to prevent the theft. It is interesting to see a change in perception of fairies because now Ariel has “purple pinions” and his fairy helpers, their bodies “half dissolved in light,” are small with “insect wings.”

A century later, fairies are small and domesticated. Now they are perceived as little pretty beings that inhabit the blossoms so loved by 19th-century ladies. The Victorians, who built factories and railways and other things inhospitable to fairies, also loved families and picturesque settings. Now fairies were like small pretty children and had wings to flit from flower to flower.

Illustrations in fairy-tale books show wings that could not possibly have held up these children—but if aerodynamically unrealistic they are now utterly charming. Cicily Mary Barker’s 1926 Flower Fairies of the Garden depicted winged little children nestling in botanically correct and beautifully painted flowers. The fairies’ faces were portraits of Miss Barker‘s sister’s kindergarten pupils. They are irresistible and, true to fairies, have had a long life—my little granddaughter loves them as much as I did.

“There are fairies at the bottom of our garden,” wrote Rose Fyleman. In her poem of that name, she described her turn-of-the-19th-century garden, with its little wood and stream “not so very very far away.” Few of us have a little wood and stream—we are more apt to have a mowed lawn. And if the grass is sprayed with herbicides, we won’t even be able to look for fairy rings, those circles of mushrooms which grow outwards, leaving a circle of less nutritious and paler grass in the middle. Biologists explain how the mushroom spores use up the essential nutrients and grow outward symmetrically, leaving a patch of paler grass that looks trodden, as if danced upon. Some people believe the fairies come during the night and hold their dances there. Some insist only on spores. But as many religions might affirm, science and magic do not necessarily have to contradict!

From what I see in garden catalogs, lots of people would like fairies in their gardens. You can buy cute little houses and toad-stools to place around the garden, and I assume some people do. One wonders, though, if that’s really what the fairies want. Not all creatures would prefer little cottages to secret places where we don’t interfere with nature, as we so like to do.

When my father died, my brother and I spread his ashes in the garden he had loved so much. We circled it slowly, taking turns. It was, as so often in England, a damp chilly day, and the misty rain seemed to mingle with the ashes as they floated onto the soaking grass. Round we went. Then round again. Already the lawn had grown long, and there were weeds in the flowerbeds. Finally, the ashes were all spread, and my father was gone.

We had, neither of us, gone anywhere near his fenced-off fairy garden. ❖

This article was published originally in 2020, in GreenPrints Issue #120.