By the time you read this I may have become the happy recipient of $15,000 per week—for life. By now my family and friends will have received generous gifts (say “Thank you,” Pat). Not too generous, though: I don’t want the people I know hobnobbing with the ultra-rich or going on one of those cruises that are so bad for the ocean (put the Hawaiian shirt away, Pat). And by now I will also have sent hefty checks to help prevent global warming, encourage gardeners, save trees, etc. A few more gift subscriptions to GREENPRINTS would be good, as well. Meanwhile, I’m taking my vitamins and eating broccoli. I’m 81—I don’t want them to get away with only a few monthly payments.

Did I mention that at the time of this writ-ing I haven’t actually got the money? And looking at the small print on this sweepstakes form I received in the mail, I see that my chances are about one in six million. So I may have to hold off some of my gifts and projects for now. (Sorry, Pat, don’t order that Heated Massage Inversion Table just yet). But you never know…

Gambling, as I suppose I should call this, goes as far back as civilization. The word “gambling” comes from the Anglo-Saxon gamon, “to sport or play.” It seems to have been practiced since at least 3500 BC, when Egyptian paintings and pottery depicted people or gods tossing astragali to predict outcomes. An astragalus is a bone in the heel of a sheep or dog (I’d want the sheep myself) that is unevenly sided, one side being round. It is sometimes called a “knucklebone.” People placed bets predicting what side would land uppermost when they threw the bone.

Later, dice were invented, and now we have elaborate machines that toss balls for lotteries. We have huge casinos for gambling. Online opportunities abound. You can bet on anything from dog racing (that’s going to go if my new millions will help) to whether your boyfriend will call, whether it will rain, etc., ad infinitum. Indeed, I know a woman who gambled away everything she had, including her house. She could not stop. Now she lives with her sister—and they fight.

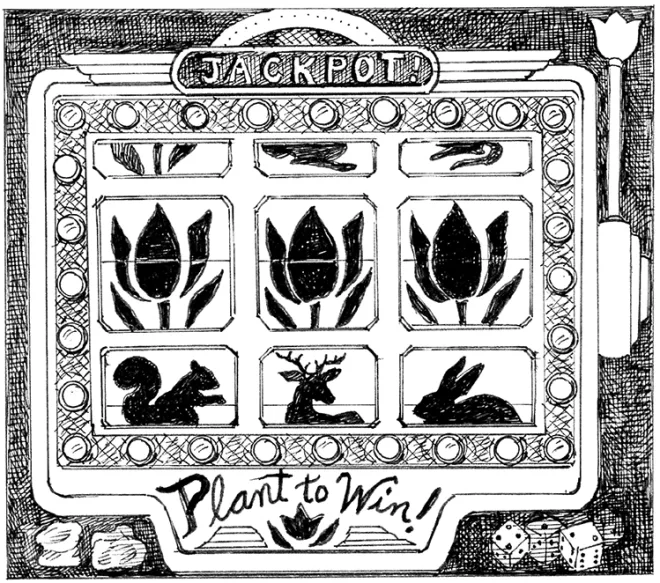

Gardeners may not gamble for money, but they do gamble all the time, measuring their hopes of success against the risks. I, for instance, received a shipment of red Dutch tulips this Fall, seduced by a magnificent photo of red tulips mixed with blue grape hyacinths in a perfect garden. The plant catalog gambled that I would take them up on their offer—and I did. Nature will decide if my gamble pays off. Tulips are definitely a gardening risk here in eastern Pennsylvania.

They became a legendary economic risk in Holland in the 17th century. Interest in rare tulips grew into a national obsession. Tulips sometimes unpredictably “break” so their petals become striped or feathery. In the 17th century no one knew why, though now the characteristic is thought to be caused by a virus. Anyway, during the Tulpenwoede (“Tulip Madness”) craze, prized tulips fetched incredible prices: one bulb of a Viceroy tulip sold for 2 loads of wheat, 4 loads of rye, 4 oxen, 8 pigs, 12 sheep, 2 hogs-heads of wine, 4 barrels of beer, 2 barrels of butter, 1000 pounds of cheese, a bed, a suit of clothes, and a silver cup. There is a famous Tulpenwoede story—one of the most famous gambling stories known—of a misled collector mistaking a prized tulip bulb for an onion. He ate it, devouring a fortune.

Tulip gambling became so frenzied that sometimes actual bulbs did not exist—they were what we now call “virtual” and passed from one speculator to another. Finally, the Dutch government intervened, and in 1637 the market crashed.

My gamble with tulips isn’t monetary, but planting them is certainly taking a risk, and I’m anxious about the outcome. Mice love the bulbs; squirrels dig them up; and even if the bulbs survive, deer eat the plants, sometimes when they are in bud and just about to burst into flame.

I could have planted daffodils instead—they have sharp crystals in their sap that prevent browsers. But I don’t want more daffodils. I want tulips. I want red ones. I want their burst of scar-let after a grey winter. I want to be told the world can dazzle us still. I want to be blinded by the glory of Spring that once again confirms our hopes.

That is why I have planted red tulip bulbs. I might be a winner and, a few months from now, have glorious blooms adorning my yard. Stay tuned.

And who knows? I might win that other bet, as well. ❖

This article was published originally in 2022, in GreenPrints Issue #128.