What brought me back was the shed, but more than that, it was the seeds. The seeds, in their crisp little handmade packets, their names written in my grandfather’s neat, cursive hand.

Every August since we were little, my sister and I went to our grandparent’s small cottage near Lake George, in the hills of the Adirondacks. Our parents trekked us up in our old station wagon, packed to the brim with all of the “essentials” the two of us would need for a month in the country. My sister, Rose, and I were keen allies, and as long as we had each other for company we were fairly contented. Grandpa filled his retirement by growing plants and crafting birdhouses, and Granny let us play freely in the woods and swim in the lakes, always coming back to a garden-fresh, home-cooked meal.

When Rose turned 17, she decided she wanted to work as a camp counselor. My parents determined that 14-year-old me could still benefit from a country sojourn, so I was sent up alone. I pleaded with my parents not to send me away. No use—I was shipped off to the middle of nowhere to fend for myself.

Grandpa had died a few years before, and the quaint cottage seemed even larger now in both his and Rose’s absence. The house was permeated with an eerie quiet upon my arrival, which I exacerbated—partly to punish my grandmother for letting my sister off the hook. For a week, I spoke as little as possible, giving curt “yes” or “no” answers to questions. I was hurting. I was upset at Rose’s absence. And the past year’s transition to high school had been rocky—childhood friends had seemingly abandoned me overnight, and I had yet to find my footing. My sister, always my confidant, was preoccupied with her friends. She no longer seemed to have a place for me in her life.

Granny sensed this loneliness in me. She tried to wait it out—for a week. But then she’d had enough.

She woke me up bright and early one morning.

“I need your help with something today,” she said briskly. This was odd. I had chores at Granny’s but I’d had them for years—make your bed, empty the dishwasher, feed the cat. I’d done them so long that I knew the routine by heart.

I pretended to be asleep, but it didn’t work.

“Grab something to eat, then come out to the shed. I need you to help me clean it out. It’s a bit of a disaster.”

She walked out of the room. The shed? I thought. I hadn’t been allowed in the shed for years. Rose and I had used it as a clubhouse for many a childhood game, always running around and causing general chaos while Grandfather worked. It was more than a shed, really. It was his special space, where he kept his gardening tools and workshop. I loved to watch him—when he planted bulbs in terra cotta pots, I imagined they were dragon eggs. After he died, quite suddenly, the shed became off limits. It now loomed on the property like a ghost’s tomb.

I threw on some clothes, headed downstairs, and dumped some food in the cat’s bowl. Then I grabbed a granola bar out of the pantry and I went to the shed.

Granny was already inside, her graying hair tied back with a red bandana, thick suede gloves protecting her hands as she used a crowbar to pry a piece of nailed wood off the window. She removed the plank with two swift movements—I was impressed!

”I thought we could use a little more light,” she said, as sun-beams pierced the dusty glass pane. I nodded in agreement.

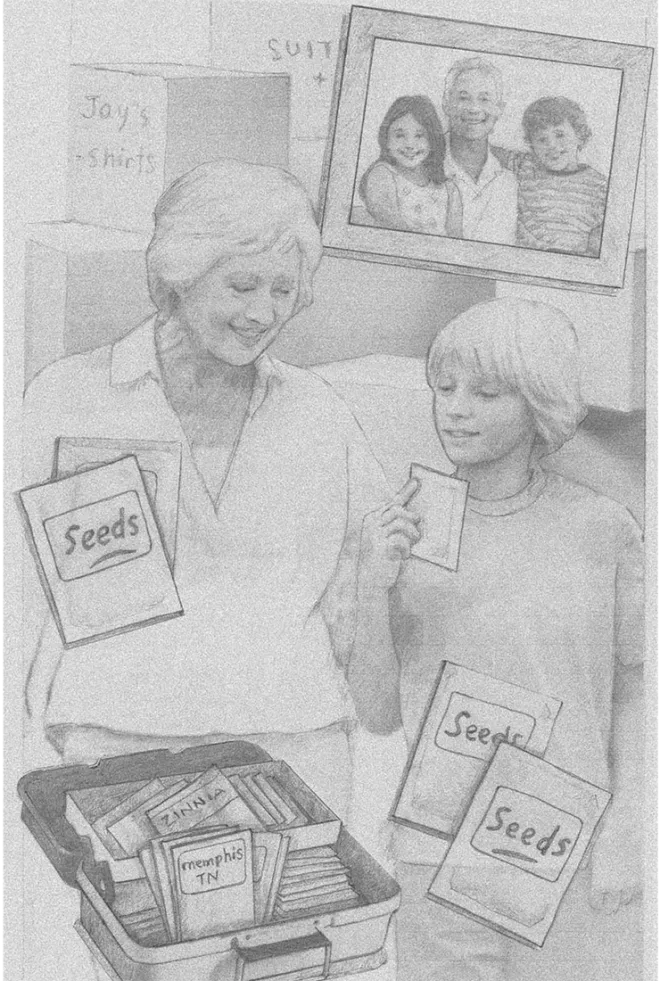

The shed was virtually unchanged since I had last been inside. I noticed a small photo of Rose and me with Grandpa in a frame I’d made back in second grade art class sitting on the desk. I walked over and picked it up, running my fingertip over our smiling, childhood faces.

“He loved you very much,” Granny said, putting a hand on my shoulder.

I pulled away—a little too quickly—at her touch and shoved my hands into my pockets.

“What do you need me to do?” I asked.

“Well, for starters, we need to organize and clear out all of this stuff.”

I looked around the shed and saw boxes labeled “Jay’s T-Shirts” and “Suit and Ties.”

“Is this all Grandpa’s?” I asked, gaining interest.

“After he passed,” Granny started softly, “I just couldn’t get rid of it. They say after a certain amount of time, you have to just toss it or donate it, but I just couldn’t.”

I suddenly understood why Granny had locked up the shed. Not only had it been Grandpa’s private spot, but it had become an inadvertent mausoleum, a time capsule of his life.

“If I was left to my own devices, I’d just leave it forever,” Granny said quietly.

“Let’s do it together then,” I replied. Granny gave me an appreciative smile. I grabbed the penknife off the workbench and opened the nearest box.

We worked for many hours, making neat piles and talking about Grandpa. Every piece of clothing seemed to incite some memory from Granny or me. Before long, we were laughing as we told stories about fishing trip disasters and marveled at how much of Grandpa’s clothing was stained with potting soil.

Just as we were finishing, I noticed a gray tackle box in the corner. I walked over and opened the lid. Inside, just as he had left them, were beautiful handmade seed packets, all labeled in his orderly cursive hand.

“Ah, his other babies,” Granny said, coming up behind me.

“If they were his babies, why did he keep them in a fishing box?” I asked.

Granny laughed. “To keep them safe, of course. Nobody would ever look for them there.”

“But they’re just seeds,” I countered. “They could easily be replaced.”

I picked up a packet that read “Hydrangea Macrophylla—Memphis, TN” and turned back to Granny.

“These are special seeds,” she explained. “They come from all over the world—from all of the places our family has lived. Those ones you’re holding are from the first year we were married, when we lived in Memphis.”

“You lived in Memphis?”

“Just for a year, but every place we’ve lived since, every hydrangea we ever planted, originated from that bush in Tennessee.”

I looked back at the box, now in amazement at its contents. “The origins of some of the seeds date back almost a hundred years. To Grandpa’s father, who brought them over from Middlesex County, Ireland.”

“Which one was his favorite?” It was suddenly important that I know.

Granny thought for a few moments. “I’m not sure he had a favorite, really. But he always used to bring me zinnias.”

I gently ran my hand over the hundred of packets and made my way to “Z.” I pulled a zinnia packet from its resting place, and held it in my hands as if it were as valuable as gold.

“Can we plant some?” I asked.

Granny smiled. “I thought you’d never ask.”

“A pot for you, and a pot for me.”

“And what about Rose?” she countered. “Shouldn’t we plant some for her, as well?”

“OK. She can take it to college with her, though I don’t know if she’ll be able to keep it alive.”

“Don’t worry, we’ll teach her. You’ll be an expert by the time you go home.”

I took four terra cotta pots off a shelf and put them down on the workbench.

“Four?” Granny asked, puzzled.

“Grandpa needs one, too,” I said. ❖

This article was published originally in 2016, in GreenPrints Issue #106.