As a child, I lived next door to my grandmother, so I came to know her pretty well. She loved her flowers. She had flowerbeds around her house. There were rows and rows of irises. And beautiful peonies lined her driveway all the way to the road.

One day, I was weeding the iris with Gram and—I suspect—starting to slow down, when out of the blue she said, “Connie, did I ever tell you about my neighbor Jennie’s note-toting hens?”

My eyes brightened. “Note-toting hens, Gram?” I said.

“Yes, and how they saved our friendship?”

My eyes got wide. “No, ma’am!”

“Well, let’s keep on weeding, shall we? And I’ll tell you all about it.”

I dug my hands back into the iris bed, and Gram began.

Before your grandpa and I moved to the country, we lived in a little house in town. Back then people were allowed to keep chickens in their backyard. A hen lays about an egg a day, you know.

One day my neighbor, Jennie, told me she’d just purchased a dozen chicks, and they’d be laying eggs in about six months. It sounded like a good idea to me at the time—but that was before I knew how much trouble hens could bring.

A few months later, Jennie began letting them out of their pen each morning to feed around her yard. “Free-roaming hens produce more nourishing eggs,” she told me. “They eat bugs and worms for protein.”

Within a week they weren’t content feeding in her yard, but preferred to come over to mine. And the place they wanted most to scratch for their bugs and worms was among my flowers. Their big, clawed feet dug deep holes next to my plants, exposing and drying the roots, and causing some of my perennials to die. I was chasing them back home throughout the day and filling the holes they’d dug at night. And of course, as soon as I’d walk away they’d come right back to my garden.

My garden was getting destroyed, but I couldn’t say anything to Jennie about it because I didn’t want to risk offending her and losing her as a friend. I do love my flowers, but keeping our friendship meant more. I didn’t know what to do!

Then one night, while I was preparing sweet corn for dinner, an idea popped into my head. When the dishes were washed, I grabbed a needle and thread and fastened a piece of string to a kernel of corn. Then I attached a little folded-up note to the other end of the string. I made about a dozen of these notes on a string and set them out in my flowerbeds.

Now I knew the hens wouldn’t be hurt by swallowing the corn and string. Chickens have what’s called a crop in their neck where their swallowed food goes first. This crop holds bits of gravel they pick up throughout the day which they use to grind their food a bit before it travels down into their stomachs. So after the kernel was pre-ground in a hen’s crop, the note and string would be free and would fall right out of its mouth.

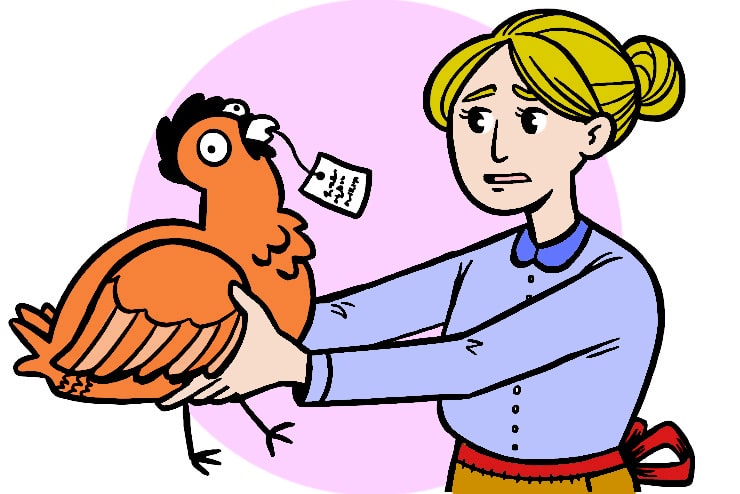

That evening I watched the hens trot back to their henhouse. What a sight it was. My little notes dangled from the beaks of several of them, waving like flags at the sway of the hens’ heads as they scurried back home.

The next morning Jennie dropped in for coffee, as was her habit. “You devious devil,” she said. “Last night when I went out to lock the hens in for the night, I saw them all lined up on the roost … and some of them had little bits of paper dangling from their beaks! I pulled on one—it came right out of the hen’s mouth—and read: ‘I’ve been digging in Ms. Jewell’s flower beds.’”

Jennie burst out laughing—and, relieved, so did I. We laughed and talked together a good while, then figured out how to solve the problem by installing a fence between our yards. That kept Jennie’s hens at home—and helped me keep Jennie as my friend.

The next Summer I came to appreciate Jennie even more. This was 1918, and your grandpa came down with a very dangerous influenza. It was so contagious that our household was put under strict quarantine. A sign was posted on our door, stating that no one was to enter or exit the house for two weeks. I couldn’t go out to buy anything at all. And back then, we had no freezer in which to store our food. My good friend Jennie volunteered to shop for us and to pass groceries to me through my kitchen window. She did this for two whole weeks.

My advice to you, young lady? Value a good, true friend, and work hard at keeping her.

When Gram finished her story, we went inside for lunch. While she fixed it, I hunted around and found a piece of string and a small bit of paper. I wrote, “I love you, Gram,” on the paper and folded it up. Then I tied it to the string, put the free end of the string in my mouth, and went back to kitchen. As soon as Gram saw me, I flapped my bent arms and clucked gently (as best as I could with my mouth closed!)

Her eyes brightened. ❖