Richard Powers’ The Overstory is an absolutely beautifully written novel about trees. Well, it’s also about the adventures of people trying to preserve and protect them, how they got involved in this battle, and why it’s important. The book works in great information about how trees communicate along with high drama and wonderful characters (so many that at times things can get a wee confusing). Powers deserves to be called the Herman Melville of trees.

I’ll share part of his introduction to just one main character here.

It’s 1950, and like the boy Cyparissus, whom she’ll soon discover, little Patty Westerford falls in love with her pet deer. Hers is made of twigs, though it’s every bit alive. Also: squirrels from pairs of glued walnut shells, bears made of sweetgum balls, dragons from the pods of Kentucky coffee trees, fairies donning acorn caps, and an angel whose pine-cone body needs only two holly leaves for wings.

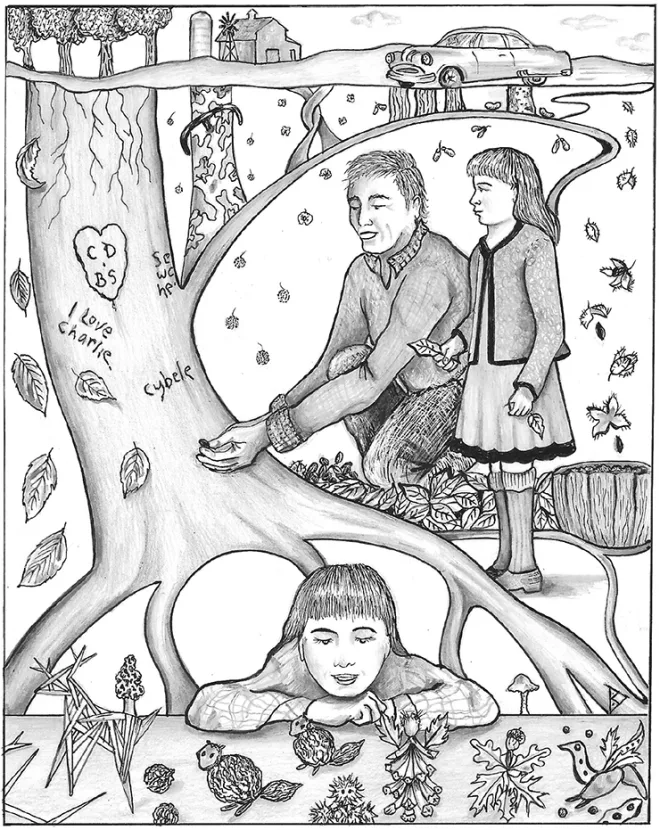

She builds these creatures elaborate homes with pebbled front walks and mushroom furniture. She sleeps them in beds fitted with magnolia-petal comforters. She watches over them, the guiding spirit of a kingdom whose towns nestle behind closed doors in the burls of trees. Knotholes turn into louvered windows, through which, squinting, she can see the inviting parlors of woody citizens, the lost kin of humans. She lives there with her creatures in the minuscule architecture of imagination, so much richer than the offerings of full-sized life. When her tiny wooden doll’s head twists off, she plants it in the garden, certain it will grow another body.

All her twig creatures can talk, though most, like Patty, have no need of words. She herself said nothing until past the age of three. Her two older brothers interpreted her secret language for their frightened parents, who began to think she must be mentally deficient. They brought Patty into the clinic in Chillicothe for tests that revealed a deformation of the inner ear. The clinic fitted her with fist-sized hearing aids, which she hated. When her own speech started to flow at last, it hid her thoughts behind a slurry hard for the uninitiated to comprehend. It didn’t help that her face was sloped and ursine. The neighbors’ kids ran from her, this thing only borderline human. Acorn people are so much more forgiving.

Her father alone understands her woodlands world, as he always understands her every thickened word. She has a pride of place with him that the two boys accept. With them, Dad may throw softballs and tell bubble-gum wrapper jokes and play tag. But he reserves his best gifts for his little plant-girl, Patty.

Their closeness bothers her mother. “I ask you. Has there ever been such a little nation of two?”

Bill Westerford takes Patricia with him when he visits southwestern Ohio farms on his tours as an ag extension agent. She rides copilot in the beaten-up Packard with the pine side paneling. The war is over, the world is on the mend, the country is drunk on science, key to better living, and Bill Westerford takes his daughter out to see the world.

Patty’s mother objects to the trips. The girl should be in school. But her father’s soft authority prevails. “She won’t learn more anywhere than she will with me.”

Mile after plowed mile, they hold their roving tutorial. He faces her so she can read his moving lips. She laughs at his stories — thick, slow booms—and stabs enthusiastic answers to each of his questions. Which is more numerous: the stars in the Milky Way or the chloroplasts on a single leaf of corn? Which trees flower before they leaf, and which flower after? Why are the leaves at the top of trees often smaller than those at the bottom? If you carved your name four feet high in the bark of a beech tree, how high would it be after half a century?

She loves the answer to that last one: Four feet. Still four feet. Always four feet, however high the beech tree grows. She’ll love that answer still, half a century later.

In this way, acorn animism turns bit by bit into its offspring, botany. She becomes her father’s star and only pupil for the simple reason that she alone, of all the family, sees what he knows: plants are willful and crafty and after something, just like people. He tells her, on their drives, about all the oblique miracles that green can devise. People have no corner on curious behavior. Other creatures—bigger, slower, older, more durable—call the shots, make the weather, feed creation, and create the very air.

“It’s a great idea, trees. So great that evolution keeps inventing it, again and again.”

He teaches her to tell a shellbark from a shagbark hickory. No one else at her school can even tell a hickory from a hop hornbeam. The fact strikes her as bizarre. “Kids in my class think a black walnut looks just like a white ash. Are they blind?”

“Plant-blind. Adam’s curse. We only see things that look like us. Sad story, ain’t it, kiddo?”

Her father has a little trouble with Homo sapiens himself. He’s caught between fine folks whose family farms are failing to subdue the Earth and companies that want to sell them the arsenal to bring about total dominion. When the frustrations of the day grow too much for him, he sighs and says, for Patty’s impaired ears alone, “Ah, buy me a hillside that slopes away from town.”

They drive through a land once covered in dark beech forest. “Best tree you could ever want to see.” Strong and wide but full of grace, flaring out nobly at the base, into its own plinth. Generous with nuts that feed all comers. Its smooth, white-gray trunk more like stone than wood. The parchment-colored leaves riding out the winter—marcescent, he tells her—shining out against the neighboring bare hardwoods. Elegant with sturdy boughs so much like human arms, lifting upward at the tips like hands proffering. Hazy and pale in spring, but in autumn its flat, wide sprays bathe the air in gold.

“What happened to them?” The girl’s words thicken when sadness weighs them down.

“We did.” She thinks she hears her father sigh, though he never takes his eyes off the road. “The beech told the farmer where to plow. Limestone underneath, covered in the best, darkest loam a field could want.”

They drive from farm to farm, between last year’s blights and next year’s vanishing topsoil. He shows her extraordinary things: the spreading cambium of a sycamore that swallowed up the crossbar of an old Schwinn someone left leaning against it decades ago. Two elms that draped their arms around each other and became one tree.

“We know so little about how trees grow. Almost nothing about how they bloom and branch and shed and heal themselves. We’ve learned a little about a few of them, in isolation. But nothing is less isolated or more social than a tree.”

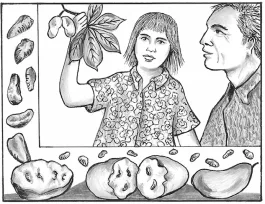

Her father is her water, air, earth, and sun. He teaches her how to see a tree, the living sheath of cells underneath every square inch of bark doing things no man has yet figured out. He drives them to a copse of spared hardwoods in the bottoms of a slow stream. “Here! Look at this. Look at this!” A patch of narrow stalks, each with big, drooping leaves. A sheepdog of trees. He makes her sniff the giant spoonlike foliage, crushed. It smells acrid, like blacktop. He picks up a thick yellow pickle from the ground and holds it to her. She has rarely seen him so excited. He takes his army knife and cuts the fruit in half, exposing the buttery pulp and shiny black seeds. The flesh makes her want to scream with pleasure. But her mouth is full of butterscotch pudding.

“Pawpaw! The only tropical fruit ever to escape the tropics. Biggest, best, weirdest, wildest native fruit this continent ever made. Growing native, right here in Ohio. And nobody knows!”

They know. The girl and her father. She’ll never tell anyone the location of this patch. It will be theirs alone, fall after prairie-banana fall.

Watching the man, hard-of-hearing, hard-of-speech Patty learns that real joy consists of knowing that human wisdom counts less than the shimmer of beeches in a breeze. As certain as weather coming from the west, the things people know for sure will change. There is no knowing for a fact. The only dependable things are humility and looking.

He finds her out in the backyard making birds from the twinned wings of maple samaras. An odd look comes over his face. He holds up one of the seeds and points it toward the giant that shed it. “Have you noticed how it releases more seeds in updrafts than when the wind is blowing downward? Why is that?”

These questions are her favorite thing in the world. She thinks. “Travels farther?”

He puts his finger to his nose. “Bingo!” He looks at the tree and frowns, working through old puzzlements all over again. “Where do you think all the wood comes from, to get from this little thing to that?”

Wild guess. “The dirt?”

“How could we find out?”

They design the experiment together. They put two hundred pounds of soil in a wooden tub by the south face of the barn. Then they extract a three-angled beechnut from its cupule, weigh it, and push it into the loam.

“If you see a trunk carved full of letters, it’s a beech. People can’t help writing all over that smooth gray surface. God love ’em. They want to watch their lettered hearts growing bigger, year after year. Fond lovers, cruel as their flame, cut in these trees their mistress’ name. Little, alas, they know or heed how far these beauties hers exceed!”

He tells her how the word beech becomes the word book, in language after language. How book branched up out of beech roots, way back in the parent tongue. How beech bark played host to the earliest Sanskrit letters. Patty pictures their tiny seed growing up to be covered with words. But where will the mass of such a massive book come from?

“We’ll keep the tub moist and free of weeds for the next six years. When you turn sweet sixteen, we’ll weigh the tree and the soil again.”

She hears him, and understands. This is science, and worth a million times more than anything any person might ever swear to you. ❖

Reprinted from The Overstory by Richard Powers. Copyright ©2018 by Richard Powers. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.