What is it with seeds? Why are lettuce and carrot seeds so ridiculously teeny that the instructions on the package (“plant three to four inches apart in rows”) make no sense unless you’ve got fingers like a leprechaun? Why can’t everything be the easily grabable size of—say—beans? Or walnuts? Or avocados?

It turns out, biologically speaking, that that’s a complicated question.

Seed size, scientists guess, is a survival strategy trade-off. That is, for a plant’s best chance of making it into the next generation, it can either plump for gazillions of small seeds—the strategy favored in the animal kingdom by frogs—or go for just a few hefty, nutritionally packed seeds, the strategy favored in the animal kingdom by us.

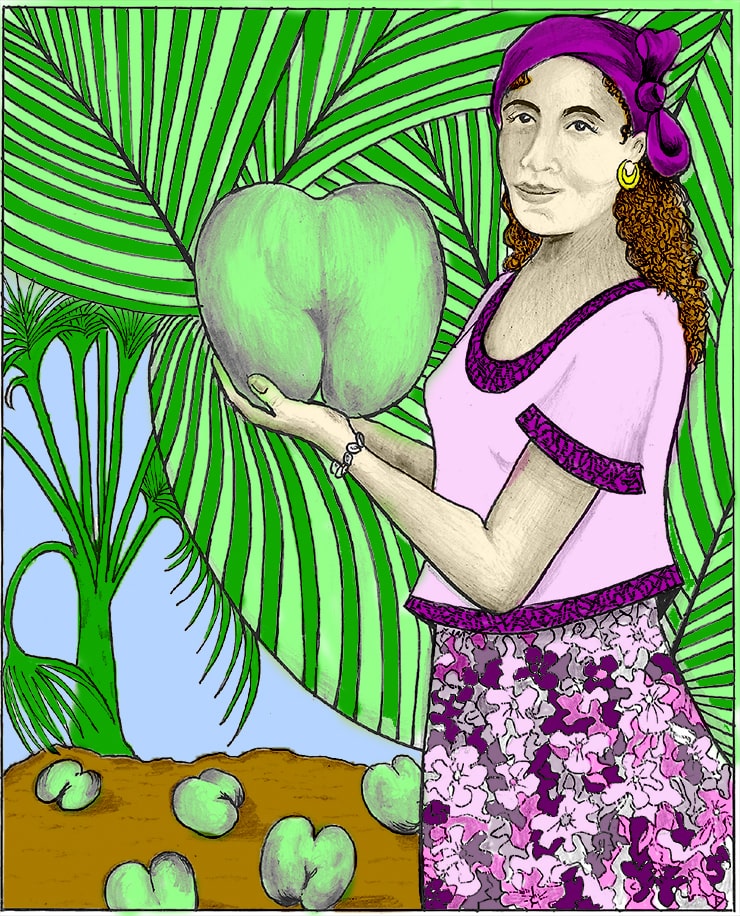

Chances are, if we were plants, we’d be Lodoicea maldivica, commonly known as coco de mer or sea coconut. The coco de mer is a coconut palm native to a couple of islands in the Seychelles. Its massive seed, which looks remarkably like a human bottom (an archaic botanical name was L. callipyge, from the Greek for “beautiful buttocks”), is a foot long, and the largest discovered to date weighed in at 55 pounds. Our theoretical opposite number, the almost-invisible seeds of tropical orchids, may be as minuscule as 1/300th of an inch long—think talcum powder—and weigh practically nothing.

Whatever plants decide to do, seed-size-wise, once they’ve made up their minds, they tend to stick with it. Seed size was once believed to be so reliably reproducible that seeds were used as commercial units of weight. In ancient times, the poster child for such weight standards was the carob seed, offspring of Ceratonia siliqua, a locust tree native to the Mediterranean. Carob seeds, most popularly, were used to weigh gemstones; our modern word “carat” derives from “carob.” The Smithsonian’s whopping 45.5-carat Hope Diamond, in other words, equals 45.5 carob seeds.

Actually, there’s some waffle in the weights of carob seeds—entire scientific papers have been written about this, snarkily pointing out that carob seeds, weight-wise, are no more reliable than anything else. In fact, one suspicious author explains, there’s enough variation in carob that it would have been perfectly possible for less-than-honest jewelers to keep on hand batches of heavy-ish and light-ish seeds, capable of tilting the scales in any desired direction. The average carob seed, however—as determined by finicky British seed assessors in 1871—weighs 200 milligrams, which is the number used today to calculate the worth of bling.

There’s more than that, however, in the small seeds vs. large controversy. Predators play a role here: If there’s a major chance that most of your output is going to be eaten, it may make sense to go with huge numbers of tiny offspring, in hopes that a lucky handful will survive to grow another day. Similarly, small seeds have a better chance of dispersal over a wide area—little stuff scatters better—which also gives a survival boost. And studies show that small seeds grow faster—look at radishes—which means a chance of multiple crops per growing season and (yes!) even more seeds.

Big seeds, on the other hand, with their hefty packages of embryo-supportive protein, have a better start in life, being better equipped for initial survival on their own. Big seeds have an advantage in stressful conditions—which, to a seed, means shade or drought—and big seeds have a better chance of surviving at-tack by predators. That is, if you’re large enough, you can survive a little chewing.

Some big seeds evolved with eating in mind. Take, for example, the avocado, a native of Central and South America. The avocado did not evolve to satisfy our passion for guacamole; instead it developed to tempt the giant mammals of the Cenozoic Era, animals capable of gulping down an avocado whole and later, somewhere else, cheerfully eliminating its sizeable central seed. Avocado seed distributors included Megatherium, the giant ground sloth, which weighed four tons and was as tall as a giraffe; Glyptodon, an armadillo the size of a Volkswagen Beetle; and the gomphotheres, proto-elephants with four sets of tusks.

About 13,000 years ago, the Pleistocene extinction did in this happy partnership. Large mammals died off all over the world, including mammoths and mastodons, saber-tooth cats and dire wolves. South America lost 83% of its large animals, including all the above-mentioned avocado eaters. Without them, scientists aren’t sure how the abandoned avocado managed to survive; it’s possible that jaguars may have scattered a few seeds and that squirrels buried a few here or there. Today, however, we know that avocados are still around because of human beings, who put a stick in evolution’s eye by propagating and tending the trees. Which is another thing about big seeds: Sometimes they need help.

Which brings us back to the coco de mer, our plant alter ego.

The coco de mer is a dioecious tree—that is, there are male trees, which produce pollen from yard-long catkins, and female trees which, post-fertilization, produce the world’s largest seeds. Coco de mer seeds never fall far from the tree. The ripe seeds sink like stones in water, which means that they can’t get off their island, and once they thunder to the ground, they’re stuck in the parental shade on the poor soil of their isolated habitat. They survive only because their parents take care of them.

The coco de mer—perhaps alone of all in the plant kingdom—nurtures its babies. The huge, pleated leaves of the parent trees tip to funnel water down the trunks after rainstorms, collecting nutrients along the way and depositing all in the soil at the base of the tree. There the trees themselves create an enriched soil that provides a fertile ground for young developing coco de mers. It’s a strategy so successful that the coco de mer is the dominant tree on its two islands. As we all know, when it comes to child-rearing, good parenting practices help.

Not that I’ve got anything against all those tiny-seeded lettuces, carrots, and radishes, mind you—it takes all kinds to make a world, and even those feckless orchids have their place.

But I like big seeds. They’re more like us. ❖

This article was published originally in 2018, in GreenPrints Issue #114.