Much though I love the book, as a scientist I’ve always been suspicious of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden.

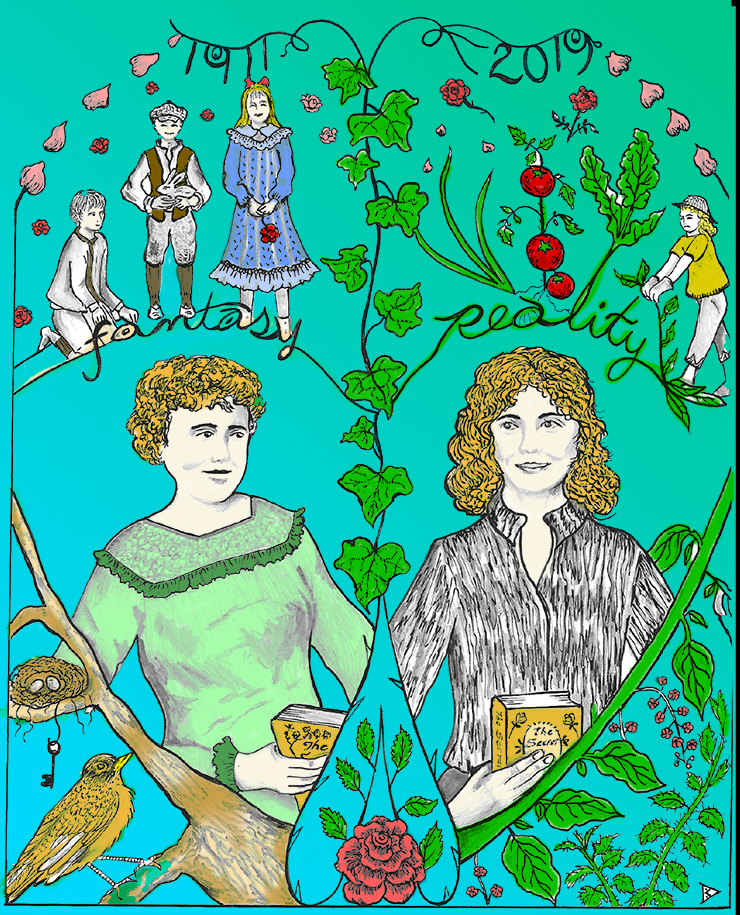

For those gardeners who haven’t read it, this is the story of ten-year-old Mary Lennox, possibly the world’s most disagreeable orphan. Mary, who lost her parents in a cholera epidemic in India, is shipped back to England to Misselthwaite Manor, a vast gloomy mansion on the Yorkshire moors, home to her uncle Archibald Craven who—somewhat understandably—wants nothing to do with her. Mary is every unpleasant British imperial stereotype rolled into one skinny, scowling bundle. She refuses to dress herself, spurns her porridge, and yells at the chatty but baffled (who wouldn’t want porridge?) maidservant, Martha, calling her the daughter of a pig.

The original title of the book was Mistress Mary, from the nursery rhyme “Mistress Mary, quite contrary/How does your garden grow?” Which suits her. Mary—no two ways about it—is an obnoxious brat.

Mary’s alter ego is Uncle Archibald’s son, her cosseted cousin Colin, a tantrum-prone invalid, whose mother died when he was born. Colin, also ten, is convinced that he’s turning into a hunchback, spends his days confined to bed, and screams whenever his will is crossed. Everyone is scared of him, including the housekeeper and the doctor. Mary is a mean little beast, but Colin is a mini-Caligula.

This unpromising pair is turned around by Martha’s odd but adorable younger brother Dickon, who has a talent with plants and animals—and by the discovery of the secret garden.

The garden once belonged to Colin’s mother, the late Mrs. Craven, and when Mary discovers it, she finds only a locked door in the wall, shrouded in ivy. A helpful robin, however, shows Mary the hidden key, and Mary slips inside to find a gorgeous, if some-what overgrown, rose garden. As the three children work together to bring the garden back to life, Mary and Colin heal themselves as well, and there’s (spoiler alert) a healthy, happy ending.

Though now a children’s classic, The Secret Garden, first published in 1911, began life as a dud. Burnett’s other children’s books, Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886)—which led to a generation of little boys being named Cedric and stuffed into velvet suits with lace collars—and A Little Princess (1905), the story of young Sara Crewe, who remained brave and cheerful, even after being plunged into poverty—were far more popular, possibly because Cedric and Sara were much nicer children than Mary and Colin. In the end, however, The Secret Garden has come out ahead. In a recent poll of the all-time top 100 children’s novels, it ranked #8, beating out Anne of Green Gables, Little Women, and Winnie-the-Pooh.

I think it’s because of the garden.

That garden is everybody’s dream space. I’m willing to put up with any number of horrible orphans and entitled invalids to find out what’s on the other side of that hidden door.

The secret garden, it turns out, was real. Burnett, in 1898, facing awful publicity surrounding an impending divorce, fled to England where she rented a vast Misselthwaite-ish manor in Kent called Great Maytham Hall. She described it as a “charming place,” complete with library, billiard room, morning room, smoking room, drawing room, dining room, eighteen bedrooms, extensive stables, and a tower on the roof with a view of the English Channel. It also had a mysterious enclosed garden, with a wall so covered in ivy that no door could be found. Eventually—with the help of a perspicacious robin (really)—Burnett tracked down the door and, behind it, found the remains of an 18th-century garden. She planted it in roses.

A decade later inspiration ensued, and she wrote a book about it. But does The Secret Garden make sense? How long do gardens last?

The truth is, not very. Once their gardeners are gone, untended gardens go down fast.

The Empress Josephine, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, spent the last years of her life planting one of the most famous rose gardens in the world at her home at Malmaison outside Paris. Even at the height of the Napoleonic wars, English gardeners were granted safe passage if they were bringing new plant specimens for Josephine’s garden, and the French Navy was ordered to confiscate any roses they might encounter on ships at sea. After the Empress’s death in 1814, however, the neglected garden—with its 250 varieties of roses—essentially disappeared.

I, a periodically shameful gardener, have seen the demise of gardens firsthand. You know what I mean. You’ve gone on vacation. You’ve been busy (writers—me—have deadlines). You’re painting the house. There’s a family reunion. Somebody’s getting married in someplace far from Vermont. Or having a baby (ditto). Or it’s really, really hot outside.

And in a matter of neglectful weeks, the garden is a mass of towering weeds, the sort that require machetes. Weeds that Tarzan could swing through, shouting for Cheetah.

I can’t help but wonder, as a cynical adult, how Burnett’s secret garden survived. She does her best to explain by adding the curmudgeonly estate gardener Ben Weatherstaff—who, she tells us, has been sneaking over the wall for years to do a bit of weeding and pruning. But this is a whole garden and Ben, due to rheumatism, admits that he hasn’t had a look-see in two years. The secret garden should have been a bramble-infested mess. Forget all those cute little rakes and spades the kids somehow managed to acquire. Mary, Colin, and Dickon should have had chain saws.

But as a lover of The Secret Garden, I’m willing to let common sense take a leap.

There’s more to gardens than the everyday, the gardens that give us tomatoes and onions and beets. There’s a magic and a romance to gardens, too, and a world of imagination. There’s more to gardens than biology. There’s wonder.

Because who doesn’t dream of someday finding a hidden door into their own secret garden?

And who doesn’t believe that there will be roses there? ❖

This article was published originally in 2019, in GreenPrints Issue #119.

The Secret Garden was one of my absolute favorites growing up, so I am willing to take that leap! Thank you for sharing!