We have a lot of books. I’ve never actually counted them, but all told, they might just possibly add up to several million, since all the walls in my office are full of them, and most of our furniture seems to consist of bookcases. We’ve also got books on bedside tables, on the floor, in the bathroom, in the basement, on the kitchen counter, and on the staircase, which makes for evil language and fancy footwork by people going up and down.

Doomsayers have expended considerable time and ink predict-ing the death of the book, what with the rise of the Internet and the e-book and the fact that surfing is giving us all the attention spans of fruit flies, but you couldn’t tell by us. When asked why we have so many books—as opposed to, say, a decent set of silverware or a yacht—we’ve taken to pointing out that, since many of our bookshelves are on outside walls, books probably boost the R-value of the house; also we’ll have an edge when the apocalypse comes, since not only will we have all those homecanned tomatoes, but we’ll be able to look practically anything up. In the end times, if anybody needs to know how to cook an eel or build an igloo, I’ll be there for you. I can also loan you the complete works of Agatha Christie in paperback.

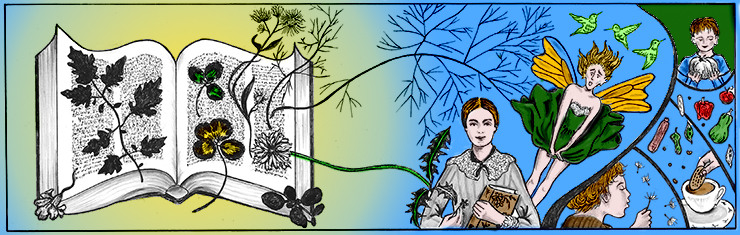

Periodically, in moments of lifestyle reorientation, we give books away, though I can’t say this really helps much, since they always seem to ooze back again. In our last weeding of the bookshelves, however, I discovered that we have an herbarium.

An herbarium is a collection of dried plant specimens. People have been amassing these since at least the 15th century. The idea seems to have originated with an Italian physician named Luca Ghini, who flattened plants between pieces of paper and then glued them onto cardboard. Generations of botanists followed suit. Today there are well over 100 million herbaria worldwide, with the largest at Kew Gardens in England, which boasts some 6,500,000 dried plant specimens. In its professional incarnation, the herbarium provides data for the studies of plant taxonomy and geographical distribution and—depending on herbarium age—a record of plant changes over time.

Making herbaria, however, also turned out to be a fun thing for the average person, since all it takes is to collect one’s favorite plants and then squish them like paninis, either in a plant press or sandwiched between sheets of waxed paper and stuffed into a large and heavy book. Pressed flowers were popular among the Victorians, many of whom kept botanical scrapbooks. Emily Dickinson, as a teenager at Amherst Academy, was an herbarium-maker. In a surviving letter, she writes to a friend:

“Have you made an herbarium yet? I hope you will if you have not, it would be such a treasure to you; most all the girls are making one. If you do, perhaps I can make some additions to it from flowers growing around here.”

Emily’s herbarium ran to 65 pages, with a total of 424 specimens; one particularly adorable page contained eight kinds of violets.

Our herbarium, it turns out, was in Volume E of the World Book Encyclopedia.

If there’s anything that’s taken a hit in the digital age, it’s the encyclopedia. The Encyclopedia Britannica—after 244 years in the knowledge business—closed up shop in 2012; what’s left of it now is wholly online. World Book, which in its heyday had 40,000 salespeople selling spiffy print sets door to door, has similarly bitten the dust. Libraries are chucking their encyclopedia hard copies. Kids these days don’t use books to look up the principal products of Portugal.

And, I have to admit, I was ready to toss ours. Our encyclopedia was inherited from my parents, an elegant set in cream hardcover, which must have been purchased in the early 1960s, since when my kids used it to look up MOON, we discovered that nobody had landed on it yet. That pretty much did in family faith in the encyclopedia, though it did look nice on the bottom shelves where everybody stashes oversized books, and—it being an heirloom—I was sentimental about it.

On the other hand, shelf space in our house being at a premium, I figured the time had come to let it go. But I’d forgotten Volume E.

Volume E—excellent for plant pressing, being the fattest of encyclopedia volumes—turned out to be crammed with plants, the leftovers of a project from when our sons were small. Smashed in waxed paper somewhere between EAGLES and EYEGLASSES were a page of flat dandelions; samples of New England asters, Queen Anne’s lace, and chicory; tomato leaves from some long-gone garden; ditto cosmos, mint, and marigold; basil and dill. Red clovers. A page of grass. (Yes, grass.)

Plant-pressing isn’t a hot hobby nowadays. On most hobby lists, reading (I have to go for that) is number one; runners-up, in various order, include fishing, sewing, bird-watching, and golf. Gardening crops up eventually, but—statistics-wise—it’s not a patch on “watching TV.” Clearly, guys, we have work to do.

Herbaria, if anything, are subjects of creepy jokes. Look at Terry Jones’s Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book which is—not for the faint of heart—full of illustrations of squished fairies. And then I read that early Dutch colonists used to press hummingbirds and send them home, flat as pancakes, in letters, which right there is enough to put you off the very idea of—well—pressing anything.

Still, there’s an upside.

My gardens run together in memory. Nothing individual survives. Tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, squash: Repeat year after year. Like Dylan Thomas in A Child’s Christmas in Wales—who couldn’t remember whether it snowed six days and six nights when he was twelve, or twelve days and twelve nights when he was six—I’ve lost it. But memory is weird. We respond to triggers: One cue will set off a wave of reminiscences. Famously, Marcel Proust dunked a cookie in tea, which prompted a seven-volume memoir.

For me, Volume E’s herbarium brought back a garden year when little boys picked tomatoes, loved dandelions, and saved grass. It was a gift I never expected. It’s a book I’m never giving up.

And if you’ve got an out-dated encyclopedia—well, think about it. ❖

This article was published originally in 2017, in GreenPrints Issue #111.

I, too, am a bookie, and I find your stories refreshing. I have encyclopedias, I have Agatha in paperback, my son-in-law lives next door and is a Gardner and a gardener! I, give books away and watch the shelves fill up. God has shown me the joys of generous living! They always get filled up again. . I have an IPad and not much knowledge of how it works. For instance, I have no idea what my website is so I will leave it blank. My husband, who has Parkinson’s and dementia, and I, are in a group of godly women known as the God Squad at our church. They have graciously accepted Vern as an honorary member in their group and he looks forward to our Friday morning meetings. If the word of the Lord is true and we believe it is, then we shall be keeping a stash of seed packets around for whenever and I look forward to watching them grow and listening to stories about them.