From the author: I wrote this piece as if I was speaking of a friend. I found it easier to say what I was feeling if I stepped outside myself and approached it in this manner. I still hope to recover one day and again dig gloveless in the dirt.

My friend is a gardener, a working gardener. At garden shows, garden tours, friends’ gardens, she is working—planning, visualizing, doing. She says her own plots hang like paintings in her mind, displaying where sun lights, shade rests, and water flows. She is a hands-on, all-in gardener, who ends her day with every fingernail tinted soil black.

She sits next to me on her back porch, our feet pushing her glider on a steady back-and-forth to nowhere. It’s Sunday, and I say, “Everyone at church misses you. Maybe you’ll be up for it next week.”

“Maybe,” she replies, “but in the meantime my garden preaches to me.”

She likes to share those garden sermons with me—every seed a resurrection; every weed a trial to conquer, or flaw to accept. She has passed on to me how she grew steadfast in the face of a sometimes unsteady marriage, and peaceful while her children struggled. I remember her mourning her mother, grief bending her body in the middle of her sweet, savory herbs. I marveled as the steady bombilation of bees and the sun’s even heat calmed her frantic heart. And I’ve seen her rise again, a new shoot from a cracked, dry hull, assured that all would work together for good—that she would overcome.

She tells me it’s the resilience of the plants that convinces her of eternity. Because of the garden, she doesn’t hold to the idea that life is fragile, but instead is quite sturdy.

She and her garden have always worked collectively—two ever-changing partners humming with life and activity. They gave to each other, friends, and family. But now their collaboration is halted. My friend’s body is failing.

She’s been sick for a long time and, as a result, so is her garden. She knows that without her ministrations it is getting lost, fading into the lawn like an old grave.

She grips her sweater tight across her chest. “There’s not enough sun to warm me up anymore,” she says.

“Wait a sec.” I run into the house and return with a blanket, tucking it up to her chin. “You look like a caterpillar,” I say.

“Good, maybe I’ll make my way out of this cocoon and get some life back.”

“You will,” I assure her, but when I sit back down, I see again the sagging remains of her garden. I stare at my lap, concentrating on the soft drone of insects and the different ways they chirp, buzz, and click, attempting to focus on anything but loss.

I know what she is missing. I am a gardener, too. I know she hasn’t made it to her horticultural church in a while, and I can’t imagine the ache—the kind that lands in your chest and spreads to the tips of your limbs when you long for someone who is out of reach. Maybe, I think, this is just a time to rest and replenish, to soak up a few more ideas. I hope.

I never saw it coming. There was little hint of an invasion at first, and she is not one to complain. Looking back, I think there were tiny grimaces, fingers massaging knees, extra deep breaths, a hand pressed to her heart. Did she stumble a little? I think so. I guess I ignored it, brushed it off as everyday aches and pains. Before I knew it, she was completely overtaken.

Her enemies were microscopic. That was part of the problem. Like rhizomes and stolons, they reached far and deep but out of sight. Down below, in the dark, warm places, they gathered strength and established their grasp. I am ashamed to say, I think I saw it in the garden first: curled, yellow leaves, a slight droop, things normally green turning brown. Disheveled and heading toward wild, her plots were trying to tell me something. But I didn’t hear them.

Now she is overwrought, overgrown, helpless to stop the struggle—hers or her garden’s. Too weak to fend off the thieves of light and air, she watches and endures a slow strangulation.

“I could help you, you know? The offer still stands,” I say.

“I know, but I just can’t—I can’t let someone else do it.” Now she cries.

I pull her to my side, tucking her under my arm, her head on my shoulder. “I know. I get it,” I say.

My shirt is damp from her tears. She says, “I know this garden—the hidden parts, more than what everyone sees. It’s more than the harvest and blooms. People think they could come here and finish it for me and I could enjoy the view, but I know that’s not true. I know it’s always growing or getting ready to grow—always parts of it dying while others are coming alive.”

She is weeping now. Her body feels like it might come apart, so I wrap my other arm around her and hold tight. It is her sweat, skin, and sometimes blood that have fed this ground. I know what this means. Others know only what they see, not what’s going on below. Maybe it seems like nothing much to them—a temporary setback. But I am beginning to sense the deep-seated nature of her decline. Letting someone else see not just the outward flaws, those stumbles and curled leaves, but the damage taking place at the very foundation—this, I know, is unsettling my friend.

“My mind, my heart, every instinct is telling me to tend the dirt and plants. But when I try, I just can’t do it. My body won’t allow it.”

I cannot conjure a response to this, so I only stroke her hair and cry with her.

Somewhere inside, between the legions of bacteria that have marched in and taken her over, my friend remains a gardener, but this illness has stretched its roots and holds fast. She can’t spy on the unassuming earthworms and whisper thanks for their crucial, quiet work. She can’t snatch up the root-hungry grub worms and toss them to a duck. Her knees can’t bear the weight of her body. Her hands can’t push a spade into the ground. And she can’t imagine someone else doing any of it.

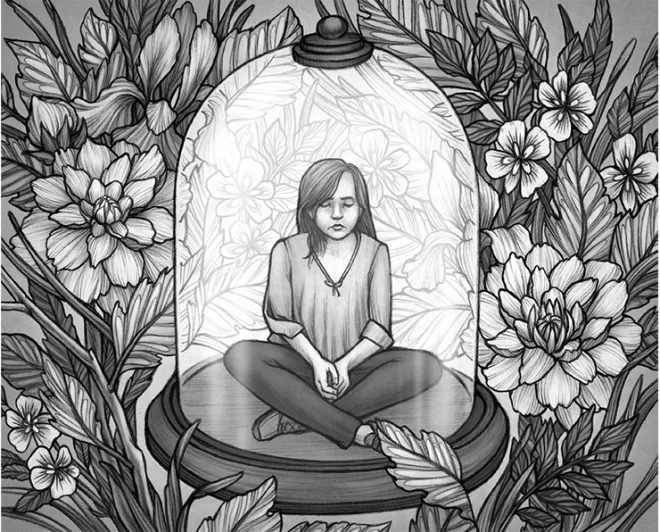

The glider stops. Her body stills, but her tears continue, soundless and hot against my shoulder. She folds into my embrace; my forehead rests against her hair. I think of my friend’s faith in the strength of life, and I believe it is valid. But it is life itself that is sturdy, not necessarily the living. We are never as strong or independent as we think.

I hear her heartbeat and keep her encased in my arms, hoping to protect the life that lingers; doing my best to believe she will open up again. But for now, no matter what is in her heart, she is a worker who cannot work, a maker who cannot make. For now at least, she is a spectator, not a gardener. ❖

This article was published originally in 2016, in GreenPrints Issue #107.