After his retirement from the bank, Mr. Kumar moved in with his son Ravi, who lived on the 17th floor of a condominium at the corner of Mumbai’s Nepean Sea Road. During the day, both Ravi and his wife toiled away at their private dermatology practice, while Neil, their son, fumbled with blocks at a day-care down the lane.

Mr. Kumar soon fell into a routine that mimicked his life in Kolkata. Every morning he undertook a walk of 35 minutes about the condominium, while his family readied themselves for their daily departures. His circle of acquaintances grew, and in time, all his fellow ramblers stopped to exchange niceties with him as they passed by. Without exception, he complimented the regulars on their figures, even if they had gained weight since he had last met them.

In between snippets of conversation, Mr. Kumar observed the residents of the flats on the ground floor. Most of them lined up a few potted plants in their windows and drew their curtains closed, to thwart passersby who tried to peek inside.

On his brief sojourns, he found little to dim his pleasure. But one morning, he noticed a thickly clustered garden of potted plants despoiling the scenery. The owners, he gathered, must have recently moved in, for he had seen a bed of dry leaves on the same lawn only the week before.

The garden stood out like a mole on an unblemished face—one of those moles that seemed to sprout new hairs with each passing glance. The sight of it annoyed Mr. Kumar—it was a blot on the hitherto pristine landscape of his ambulatory realm.

He narrowed his eyes at a cluster of rhododendrons and tiptoed closer to sneak a peek. To his surprise, the shrubbery did not resemble a wild Amazonian jungle, as he had expected from afar. Bougainvillea and gladiola flowers kissed the railing, while night jasmines and the ever-ubiquitous potted palms stood lined up in a neat row.

Mr. Singh, the neighbourhood gossip, informed him that a recently retired Colonel had moved into that ground-floor flat. Mr. Kumar grunted, and retorted that the good Colonel seemed bent on depriving his patio tiles of sunlight.

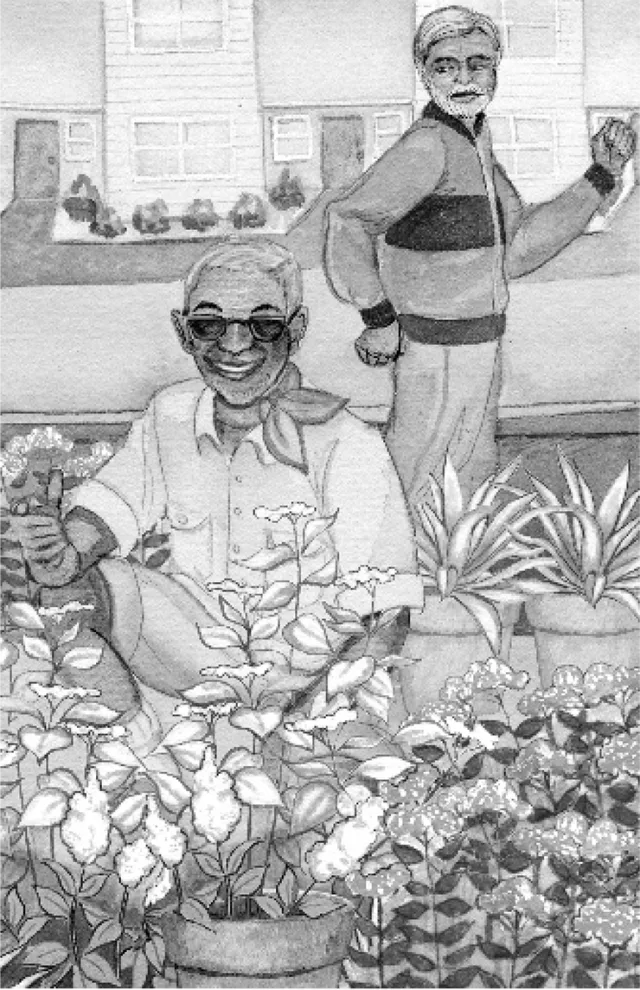

The next time Mr. Kumar strolled past the offending patch of greenery, he spotted an old man hunched over the flowers. The man was whispering, to no one in particular.

Mr. Kumar slowed down and watched from a distance. He squinted into the shadows for any sign of another person. He could see no one in the darkness between the leaves. The gentle-man must have been talking to himself, and Mr. Singh was wide of the mark about his age. The Colonel wasn’t “recently retired”—the Army had discarded him at least two decades ago. It struck Mr. Kumar, not a day less than 70 himself, that this senile old nut was talking to the plants, coaxing life into them. He laughingly imagined the chlorophyll charging up the stalks of his floral friends when the Colonel spoke to them. Would their hue turn from a dusty teal to a bright emerald simply because the old dolt uttered a few well-chosen words?

Mr. Kumar scoffed at fools like the Colonel and Prince Charles, who believed that talking to plants fostered their growth. The Colonel’s sense of style added to his disdain. The man dressed like a Boy Scout going camping, with his khaki shorts, grey shirt, sunglasses at seven in the morning, a scarf wrapped around his thick neck. Mr. Kumar himself was appropriately dressed in track pants, sneakers, and t-shirt, all sourced from the Nike factory outlet Ravi had taken him to in his first week in Mumbai.

After that, Mr. Kumar began taking a circuitous route that led away from the garden. One day, though, he turned left instead of marching straight ahead. The mistake dawned on him a second too late, and soon he faced the man who loved to potter about the foliage.

The hushed, one-sided conversation had started. Mr. Kumar strained his ears to pick up the words.

The Colonel raised his eyes and met Mr. Kumar’s gaze. Mr. Kumar did not waver and returned a fixed stare. The Colonel’s light-grey eyes bore deep into Mr. Kumar’s black ones. Mr. Kumar walked on, and a sense of relief washed over him. How like a bulldog the Colonel looked, with his bloodshot eyes and jowls hanging from his broad face.

At home afterwards, Mr. Kumar peeled and ate two oranges. He extracted their pips before popping the succulent pieces into his mouth. The news blared in the background while he ate. Then he retired to the bedroom where he researched “talking to plants” on the Internet. His daughter-in-law, Nita, had taught him to pose all his inquiries to the computer. She sat him down in front of the monitor one day and advised him to frame his questions in the little rectangle below the bizarre word “Google.”

He scoured the web for evidence that plant-talkers deserved prime placement in the local asylum, but unearthed little to back up that claim.

Days after their staring match, Mr. Kumar found his steps again marching in the direction of the Colonel’s garden. His heart beat a little faster, but as he rounded the corner, he found no one there. That wearer of shorts, flaunter of scarves, whisperer of sweet nothings, was conspicuous by his absence. Mr. Kumar leaned into the darkness between the stalks and strained to hear some sounds, any sounds, of life within the four walls of that house.

He heard nothing—no soft whirring of the fan, no chatter from the television, no humming of household activity. Mr. Kumar didn’t wait to find out if the place was indeed empty. He stepped away from the balcony railing and trudged onward.

After that, every time he passed the house, he slackened his pace. The Colonel and his family must have left their abode to holiday in an exotic location, perhaps Paris or Thailand. But then he paused. Who would talk to the plants? Who would inject them with the daily dose of chatter they apparently needed to bloom and grow?

When ten days passed and no sign of the Colonel manifested itself, Mr. Kumar made his decision. He would assume the Colonel’s role and begin speaking to the plants.

But what did one say to nonhuman living things that had life pulsing through their veins but no heartbeat? Did the plants’ growth depend on what was spoken to them? Did they reach for the sky faster if the words were to their liking?

Mr. Kumar didn’t know. He broke the ice hesitantly, tentatively, speaking about his angelic grandson who had turned a year old just last month. Did they (the plants) know that the boy’s first word was Dada, which meant grandfather in his native tongue? Such a smart boy! Why, just the other day Neil grabbed his finger and hauled his little body up for a few seconds before wobbling back onto the hard-tiled floor.

In short bursts, Mr. Kumar unravelled more stories of his grandson. When the days passed and the shrubbery showed no signs of withering, he grew emboldened and spoke of his wife. So many years since she had come into his life and then left it so abruptly, yet the moment he first met her stayed etched in his memory.

How beautiful she looked as her mother led her in for the traditional bride-viewing. She was wearing a banarasi sari with the pallu draped over her head. Her smooth, fair complexion pleased his mother, though the slight gap in her front teeth did not. The young Mr. Kumar found her dazzling and vowed to spend the rest of his life with her.

Suddenly he stopped. His eyes darted around him. What if someone overheard his confessions? He watched the plants. That was the best thing about them—like walls, they could never talk and reveal the secrets they heard. They deserved better the title of Man’s Best Friend than the canine family.

Mr. Singh almost caught him once, but Mr. Kumar pretended he had been talking on his cell phone.

“Better be careful not to hang around that Colonel’s place!” Mr. Singh warned.

“Why? What’s wrong?”

“He’s a grouchy old man. When he hired the gardener to water his plants while he was gone, he went on and on about how to do it right.”

Mr. Kumar shrugged off his friend’s warnings and began counting down the minutes to his chats with the flora. It worked, he found, like some twisted kind of therapy. Instead of lying on a couch and whining to a bored shrink who doodled while pretending to write notes, he revealed precious memories in brief but intense sessions. He didn’t know if they heard what he said—the leaves never swayed in response to his confessions. But the buds bloomed and basked in the sun’s rays.

Mr. Kumar willed his heart to continue the story of his engagement.

“Oy! What are you doing?” a voice roared.

Mr. Kumar jerked his head up, startled.

“What do you think you are doing?!”

The owner of the voice heaved into view. The Colonel looked more like a bulldog than ever, his dentures bared in a menacing grin.

Mr. Kumar spoke back. “What do you mean? I was helping you. I was—”

“I don’t need your help, you old fool!”

Mr. Kumar tottered backwards. The first words that had sprung to his mind when he thought of the Colonel was ‘old fool.’ To hear the Colonel unleash that same epithet on him shook him to the core. He let loose a flood of choicest abuses. “Imbecile! Loafer! Wearing shorts like a four-year-old!”

The Colonel matched Mr. Kumar insult for insult. The verbal storms rained down for minutes before Mr. Kumar turned homeward. He hadn’t meant to cut his stroll short, but much better to withdraw before neighbours gathered on their verandas to enjoy the show.

Nita opened the door. “Are you okay? How come you’re back before time? Are you feeling fine?”

He nodded and shuffled to the bathroom. When would she realize he was healthy? When would she stop gawking at him in alarm as if he might collapse any minute?

Tea and biscuits were laid out on the coffee table in the living room. Ravi and Nita had yet to leave for their daily grind. He leaned back in his favourite armchair and joined them.

Ravi said, “The Colonel is back.”

Mr. Kumar glanced up. “How do you know?”

“I met him in the car park when I came home yesterday evening.”

“Oh.” Mr. Kumar sipped his milky tea. “What did he say?”

“He had travelled to Delhi with his family to perform some puja for his younger son’s first death anniversary.”

Mr. Kumar absently mixed a spoonful of sugar into his cup.

Nita said, “Papa! You are not supposed to have sweet tea! You know that.”

Mr. Kumar twirled a teaspoon in his tea, lost in thought. “Only for today. I need a little sugar fix.”

She directed another worried glance at him. Ravi continued. “It seems the Colonel’s younger son was a pilot in the Air Force and died in a crash.”

Nita dipped a biscuit into her tea. “Must be one of those fighter jets that are prone to mishaps.”

“Probably,” Ravi said. “He crashed into a field to avoid civilian casualties.”

“What a tragedy,” Nita said. “He must have been so young.”

Mr. Kumar drained the last of his tea. He slipped on his socks and sneakers, grabbed his stick, and headed out the door. If he hurried, he might still have time to right past wrongs.

“Where are you going?” Nita asked.

“To finish my walk, where else?” he replied. “I have fifteen minutes remaining.” ❖