Yet still the unresting castles thresh

In fullgrown thickness every May.

Last year is dead, they seem to say,

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

—From Philip Larkin, “The Trees”

There’s no getting around the fact that these days we’re a divided nation. This year, everybody’s Thanksgiving feast and Christmas dinner almost certainly took a hit from who—politically—supports who and why and who, just as passionately, doesn’t and why not. Even our family, usually largely in accord, got a little scratchy this year as to who was most thankful for what, and who wasn’t thankful for much of anything at all.

I get that. These are tough times.

Sometimes we just don’t agree.

But that doesn’t mean—when push comes to shove—that we’re not all on the same page. We’ve got a lot to learn here from plants.

But let’s start from the beginning. Just like us, not all plants get along.

Walnut trees, for example, can be down-right mean.

The brown pigment found in walnut twigs, leaves, bark, roots, and nut hulls is called juglone—a chemical whose primary function is to kill encroaching neighbors. This murderous method of maintaining personal space is known to scientists as allelopathy, and it’s been known—or at least noticed—since ancient times. People, from the get-go, were wise to the selfish and self-promoting behavior of walnut trees. Pliny the Elder, in the first century C.E., wrote “The shadow of walnut trees is poison to all plants within its compass, and it kills whatever it touches.”

Walnut trees aren’t the only ones. Given the possibility of aggressive trees, many herbaceous plants fight back with their own takes on chemical warfare. Asters and goldenrod are toxic to yellow poplar and Virginia pine; ragweed, hawkweed, timothy grass, and buttercups attack sugar maples. Broomsedge—a tough and weedy grass—inhibits black locust seedlings. It’s also toxic to young walnuts, which shows that walnuts, though they may be the bullies on the botanic block, don’t always get their own way.

All this attack and counterattack sounds—sadly—an awful lot like us.

But there’s another side to the story.

Peter Wohlleben, German forester and author of The Hidden Life of Trees, argues that trees, rather than being disconnected loners, are members of interconnected supportive communities. And there’s some science to back him up.

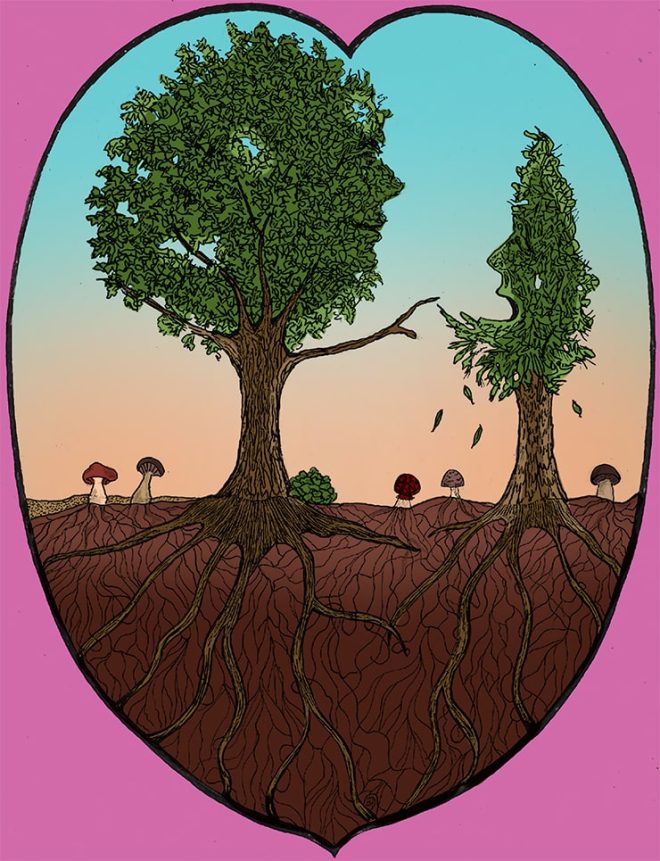

Trees bond through what scientists call a mycorrhizal network—that is, a massive underground network of fungal filaments connecting trees root to root throughout a forest. This partnership is a win-win for everybody. Fungi get food in the form of sugars from the tree’s photosynthesizing leaves. About 30% of a tree’s sugar goes to feed its fungi, and fungi, in turn, help the tree absorb more water and nutrients from the soil than it would be able to suck up on its own.

Some trees—nicknamed mother or hub trees—are exceptionally good at this, each functioning as a sort of arboreal soup kitchen. These are the biggest and oldest trees in the forest, the ones with the most widespread roots and the most extensive collection of helpful fungi. These are able to sense when surrounding young saplings are struggling, and to mobilize the fungal net to send the kids extra doses of nutrients.

Some plants would flatly starve to death without the mycorrhizal net. For example, Indian pipe (Monotropa uniflora), a bizarre relative of blueberries and rhododendrons, is pure white, for which reason it’s sometimes called the ghost flower or corpse plant. Since it contains no chlorophyll, it can’t make its own food via photosynthesis—which means it would be up a creek if it weren’t for the sugars provided for it via subterranean fungi. And it’s not alone. It’s estimated that some 400 other chlorophyll-less plants survive with help from fungal friends.

Trees also appear to communicate by sending chemical, hormonal, or electrical signals through the myccorhizal network, sounding alarms about such impending disasters as drought or invading beetles. Wohlleben—whose English is good enough to make awful puns—calls this fungal telegraph system the wood-wide web. Forests, many scientists now believe, function like hippie communes or insect colonies, with all members working together to support the group.

So, apparently, do gardens. Some experiments showed that tomatoes beset with pathogens pass the news to their neighbors through fungal connections, thus warning them to crank up production of defensive enzymes; and beans, similarly, rally their troops via the mycorrhizal network to ward off pernicious aphids.

The mycorrhizal network is both ubiquitous and enormous. Every teaspoon of soil contains miles of fungal filaments, or hyphae. Soil microbiologists guess that the global total adds up to some 30 billion tons of fungi—or about four tons’ worth for every human being on the planet. It’s also largely invisible: generally we only notice it when fungal fruiting bodies (a.k.a. mushrooms) pop up in the yard, or if we actually set out to dig for it, as happens when searching for truffles.

About 95% of the world’s land plants are connected to the mycorrhizal network—and, according to the fossil record, it’s a beautiful friendship that has been going on for more than 400 million years.

Which may be the problem with people. Our species has only been around a scant 200,000 years or so—maybe we simply haven’t learned to appreciate our invisible interdependent connections yet. Maybe we need more time. Look at the mother trees. It’s clear that nurturing networks aren’t built in a day.

But I think we’ve got potential. I think that—just like trees—we’re better off together than alone, and that the web binding us together is greater than our differences. And even if in recent years that web has frayed a bit—well, I believe that it’s never too late to begin afresh. ❖