Young lady, take Grandpa out to the garden and let him tinker around out there,” my mother called from the basement laundry room.

“All right,” I said reluctantly. I had no desire to go outside, but I had even less desire to take over the laundry.

Grandpa had gotten into a slump lately. He sat around a lot, not paying attention to much of anything. Even the television went unnoticed. Only going outside seemed to lift his spirits.

Grandpa’s Wisconsin garden had always been his pride and joy. When he lived in his own home, he transformed his small city lot into a farm with vegetables, berries, a pear tree, and a flock of chickens. Now his energies were directed toward the small vegetable garden in the corner of our yard.

I went into the living room. “Come on, Grandpa,” I coaxed. “Let’s go water the tomatoes. We haven’t had any rain in a few days.”

Grandpa mumbled something in Polish. I tried again. “Come on, Grandpa. Let’s water the garden. The plants need it. And we can pick some tomatoes. I want to make a tomato sandwich.”

This time, Grandpa paid attention. He slowly followed me to the patio, where he had a row of buckets filled with water. When there wasn’t any rain, Grandpa would fill the buckets with the hose and let the chlorine in them evaporate. This always irritated me—so much fussing around. Everyone else just watered from a hose. Why couldn’t we?

I carried two buckets out to the garden. Then we got canning jars and started watering.

Grandpa kept up a running conversation with the plants. “Little plant, are you thirsty? I give you some water. There! Enough?”

To me he said, “Get me another bucket. Ja, that’s the one. We will finish soon.”

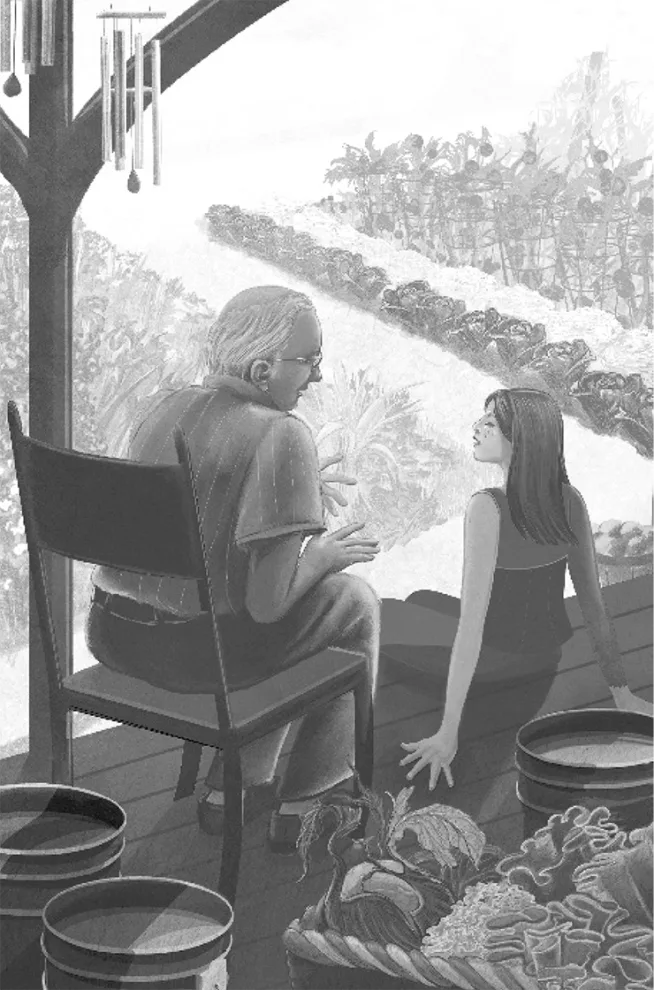

Once we finished watering, we picked the day’s crop—tomatoes, lettuce, carrots, peppers, and kohlrabi, too. When we were done, Grandpa sat on a straightback chair on the patio. I knew better than to leave him then. My mother had been adamant: “There is no reason you cannot sit out there with your grandfather. He needs the company.”

“Grandpa, tell me about the old country,” I said. If I had to sit out there, I might as well listen to something interesting.

“The old country was hard,” he answered slowly. “Why do you want to hear about that old stuff?”

“Because it’s different, and I have second cousins who still live there,” I answered.

“Ja, you do. My brother returned to Poland after the war. He didn’t like it here. He was younger than me, but he eventually married. We left Poland so that we wouldn’t get drafted into the Russian army. The Russians did not treat us too well.” He stared into the distance for a moment.

“But you were in the army, weren’t you?” I asked.

“Ja, the American army,” he said. “They put all of the Poles and the Czechs together in separate units. Sometimes our sergeants couldn’t even talk to us. We didn’t know much English back then.”

“Tell me about the man in the trench under the bridge,” I begged. It was my favorite war story.

“OK, but we go in soon. The sun is hot.” He began, “One time I was tired and afraid and crawling on my hands and knees to the next trench so that I could get some rest. The men in my unit had gotten a little spread out, and I was waiting for them. When I made it to the trench, I found a guy sleeping under the bridge. So I decided to sit next to him and rest, too. After a few minutes, I asked him a question. But he didn’t answer, so I thought he was still sleeping. Eventually I asked him another question. He didn’t answer that, either. That’s when I knew that he was not sleeping. He was dead. I had been talking to a dead man.”

“Were you afraid?” I asked.

“Afraid? Yes, but not of the dead man. The dead cannot hurt you. I was afraid of becoming like him. Enough! I want a drink of water, and you said you wanted a tomato sandwich.”

My mother winked at me when we came in. She was pleased that I had been kind.

Grandpa got his drink of water and said to my mother, “Quit worrying, Jenny. I am all right.”

That summer I spent a lot of time with my grandfather after we gardened. I learned about my grandmother, who I did not remember. I heard stories about when I was very little. Some mornings, Grandpa was a little confused. But gardening always brought him back to himself.

When the summer ended, I left for school. By the time I came back for the next summer, he had gotten worse. He had begun to talk to the man in the mirror.

We went out to water the garden, and he mumbled to the plants in Polish. One thing he said that I could understand: “Little plants, are you thirsty?”

Grandpa lived on a few more years, getting worse and worse. He took no more interest in gardening. Finally, he passed away.

Now I am a granny myself. Recently I started a raised-bed garden of my own. My Southern garden does not produce the same beautiful tomatoes that Grandpa’s garden back in Wisconsin did. But it does cause me to remember that long-ago time when I learned to be generous to a person who needed me.

And I find myself saying as I water my spindly tomato plants, “Little plants, are you thirsty?” ❖