The third time my father tried to commit suicide was the summer my mother worked hardest on our garden. He was in a mental hospital, and it was a typical Midwest Summer—hot, humid, and punctuated with thunderstorms. I was eleven years old and spending my days at the City Club, which consisted of a pool and a dingy locker room with concrete floors and showers that felt like needles, while my mother stayed home and weeded the beds of flowers and the vegetable garden.

My mother was Austrian and grew up after the war scavenging in the Alps for mushrooms, nettle, and elderberry blossoms they fried in butter if they could find someone who’d trade butter for potatoes. Now in South Bend, Indiana, she collected seeds of herbs from her visits to her stepmother in Leoben and planted them in our backyard, where they grew green and lush in the soil she made rich with cow manure she got from a farmer from Michigan (its stench used to embarrass me). With the herbs she made Kartofelknoedel, bread dumplings made of stale bread, broth, and herbs. She also planted currant bushes, and I used to pick the tiny sour berries and eat them. In August she would harvest them and turn them into jam. All year round we ate it in Palatschinken, crepes filled with jam and sprinkled with powdered sugar, or in our peanut butter sandwiches. My mother hated peanut butter but reluctantly fed it to us. She said it was like eating food that someone had chewed for you.

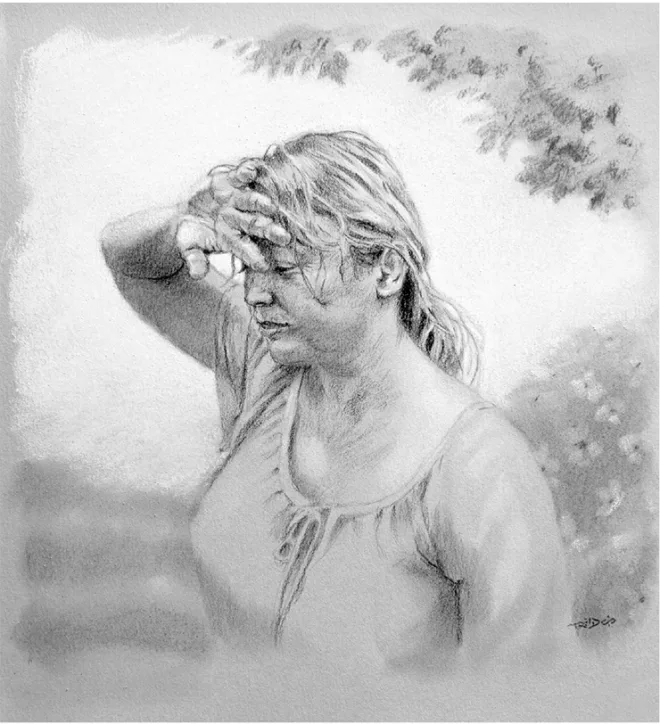

That Summer, she labored for hours weeding the flowerbeds that encircled our back lawn. She was especially proud of her roses, but the daisies, poppies, and myriad other flowers gave the frame of that yard a kaleidoscope of color. She would come into the house periodically to get another beer, her face covered in sweat, her brown strands of hair wet against her tan face, her arms muscular from all the planting and digging and weeding. She was building a world, while I spent my days swimming back and forth in chlorinated pools, coming home to eat what my mother sup-plied—carrots, tomatoes, strawberries.

Sometimes I had to visit my father, who shuffled on the dirty linoleum of the mental hospital, his lips dry and white from drugs. He gave us presents he’d crafted there. Once he gave me a hickory box he’d shellacked with a picture of a farm—a red barn, horses grazing, a field of grain ripe for the harvest.

The day he gave me that gift, we came home and my mother asked me to gather rhubarb and strawberries. She said she would make a pie for us. I went into the backyard and into the garden and swiped away the flies and mosquitoes from my face as I picked the strawberries from the rich soil. Then I went to the back, to the alley where the rhubarb nested in the weeds, with red stripes and its skin so tough and meat so sour.

I knew only my mother could turn it into something sweet. ❖