At the age of 34, Leslie Buck, a professional garden designer, went to Japan to become a pruning apprentice with a prominent landscape company. What a different—and intense—world she entered! In Japan, a 350-year-old garden may be called “not very old.” A flower arranger, asked how long he has been learning his art, might answer, “Only 15 years. I’m just an amateur.” Garden workers are respected professionals practicing a refined craft. They work very hard—six, even seven days a week. And they are almost all men.

Oh—and Leslie barely spoke Japanese!

Her memoir, Cutting Back: My Apprenticeship in the Gardens of Kyoto, offers a fascinating inside look at a horticultural world that I, for one, didn’t realize existed. Here’s an excerpt.

We worked one last day at the temple garden, which had grown cool and humid in the mornings. The senior crew members pruned trees while Masahiro and I hauled debris to a hidden area behind the garden. The company’s youngest apprentice stopped several times to instruct me on how to cut the debris into smaller pieces in order to keep the piles compact. His idea made sense, considering we only had so much space to pile the branches. But it modeled a common mistake of the inexperienced gardener. Rather than spending time tediously cutting already pruned branches, one can simply stomp hard on the pile and reduce its size in seconds. I tried to ignore Masahiro, as the men were pruning furiously and we had to move quickly to keep up. On the third lecture, I decided to obey him just to avoid another one. As I cut up branches into tiny pieces to please Masahiro, Nakaji walked by. He yelled at me, pointing to my pruning shears, and jumped on the pile of branches to show me how to reduce the pile efficiently.

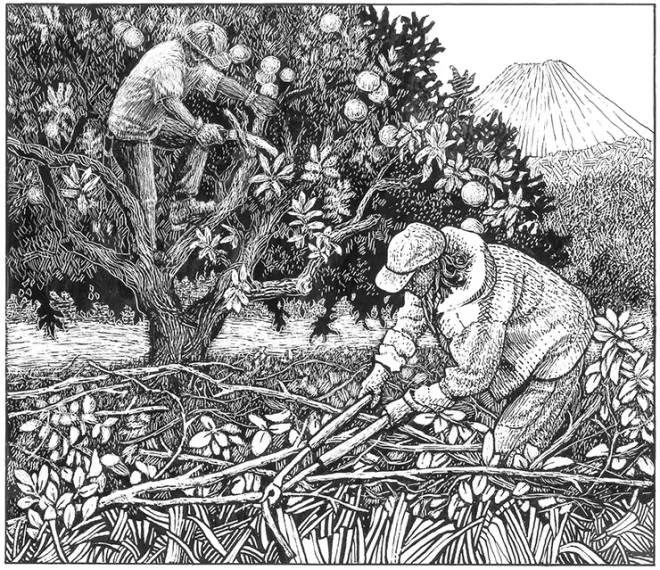

Eventually, Masahiro was asked to prune a tree and join the senior crew. This meant I had to clean up after everyone. The tree Masahiro climbed was huge, tangled, and more than twenty feet high, covered with fat glossy green leaves and fruit resembling lemons. I would later find out this was a yuzu tree, a richly scented, traditional, and coveted Japanese citrus. I felt jealous of Masahiro and ill-spirited in general. I didn’t mind the advanced workers getting to prune, but Masahiro was less experienced than I was. He’d worked only six months as a gardener, and I had seven years behind me. He had pruned his first tree only the day before. Yes, I knew that, according to Japanese craftsman hierarchy, he had seniority because he’d arrived at the company six months before me. He could tell me what to do anytime, as could anyone else who’d entered the company before I had. It felt unfair that Masahiro should get to do more advanced work when I could do it better. I eventually tried to turn the situation around in my mind by transforming myself from debris girl to power girl. I carried big loads to show the men how much I could carry at once and walked as fast as I could. That way, I breathed hard and sweated a lot, but Masahiro didn’t have time to instruct.

Masahiro’s persistence in correcting me was worrisome. I believed the men told Masahiro to give me corrections, right or wrong, because he was my sen-pai, senior worker, and I was his kōhai, junior worker. Learning how to mentor others is a key part of becoming a master Japanese craftsman. Masahiro surely would have bossed me around from my very first day if I had been Japanese. But perhaps my teenage boss just didn’t know what to do with a thirty-five-year-old American woman.

Kei told me that the company had hired its first female Japanese gardener a year before I arrived. He said the men had decided to treat her as a “regular apprentice” and that “she cried every day, for a year, until she quit and got married.” Is he warning me? My paranoia increased with my exhaustion. I felt I needed to hold my ground with Masahiro or I’d be the next one walking down the aisle—with a long garden tarp as my bridal veil.

I tried to do what Masahiro said. After all, I was in Japan to learn new ways, not to teach others. I’d make exceptions only when Masahiro told me to do something absolutely ridiculous. I’d hesitate just a few seconds before doing the task. I’d tilt my head to signal I was thinking about his words. I’d procrastinate by looking in my dictionary. Or I’d pretend I didn’t hear him at first. I figured that obeying him eventually would be enough. I’d stomp on my pile of twigs, and then, after about six reminders, I’d prune it into a million pieces. At least while he got to prune the tree, I didn’t have to obey him.

Two advanced workers took off that afternoon, so only Nakaji, Masahiro, and I were left. I realized I’d never get to do any pruning. I’d been running the debris hard for an hour, hoping for some extra time to do something more interesting. I felt defeated. Even hot coffee delivered by the monks, a real treat in green-tea country, did not lift my spirits.

Late in the day, the sun tilted against the trees, pushing clumpy dark shadows over the temple garden. Masahiro worked up in the citrus tree, getting prune-by-yell commands from Nakaji. The boss’s voice boomed over the temple garden. Way up in the tree, Masahiro frantically tried to keep up with the torrent of directions from below, yelling, “Hai! Hai! Hai!” every few minutes. I sulked in the back of the garden, jumping hard on the pile of broken branches in frustration. Then, I heard nothing. The silence continued. I looked up. Erratic footsteps came my way. Masahiro appeared out of some shrubs and quickly walked past me with a distant, cold look on his face. His arms, exposed in short sleeves, were profusely bleeding, gashes all over them. His shirt was stained with red splotches. What I didn’t know yet about a yuzu tree was that its coarse branches are covered in large, sharp thorns. It dawned on me that while Masahiro had the seeming privilege of a pruning assignment, Nakaji had given him the worst job; thorns had stabbed him at every turn.

I heard muffled noises coming from the bushes. I realized my young coworker had gone behind the debris pile to cry. My tedious complaints looked ridiculous in comparison to his determination. Nature does not always play the soft role that so many weekend gardeners rightfully and peacefully enjoy. For full-time gardeners, the midafternoon sun can be brutal when the branch you have to work on doesn’t happen to be in the shade, and plants carry thorns and sticky sap that attracts dirt and sometimes causes infection. So why was Masahiro determined to help make the thorny tree look more beautiful? Was his sacrifice because of a simple desire to acquire skill? Masahiro worked harder than what was necessary for him to learn. I saw Masahiro working with heartfelt purposefulness that day, the sort of love and care that a young parent feels for his child.

Red-faced Masahiro walked slowly past me again to return to his tree. His shoulders slumped a little, but he held his gaze purposefully forward. When I saw him coming, I rushed to climb atop the debris pile and cut the branches into small pieces like mad. How could I have thought of Masahiro as my competitor? We worked as a team, the two lowest workers. We sacrificed for each other, for the garden. After he’d climbed back up the yuzu tree, I ran over and made a show of hauling the largest and thorniest branches I could find.

Slowly, the light faded to dusk. I ran debris loads while the men pruned in earnest. Warm, sticky sweat slowly trickled from my scalp down my face. I didn’t stop to dry it off, or take time for sips of water, as I would have done in California. I needed to support my team. I jogged to and from the debris pile a bit more slowly than I had earlier in the day, but the bright citrus and busy craftsmen, my vibrant companions, kept me engaged. Nakaji’s and Masahiro’s voices echoed in the garden. The birds joined in with their dusk singsong, egging us on to walk the last mile.

Owning my own business over the past few years, I realized, had allowed my ego to grow too big, too fast. I was the boss of a business that had built up fairly quickly, making me feel quite proud and independent at an early time in my career. I pruned only small trees and plants, and rarely had to weed or get my hands in the dirt. I offered design advice to help the garden develop gracefully, and seemed to have a knack for dealing with all kinds of clients. In general, I was paid well and my clients offered only praise. True, I strived to do the highest-quality work for every garden. But most of my clients couldn’t tell the difference between good and excellent work. My mentor warned his pruning students to remain humble. “In America you are some of the best pruners. In Japan you are beginners.” I had become like a plant that had been given too much fertilizer. When a plant is overfed, it indeed grows fast. It will burst out with fresh, green, vibrant foliage. But while a heavily fertilized plant will grow big, it tends not to flower. ❖

Taken from Cutting Back. © Copyright 2017 by Leslie Buck. Published by Timber Press, Portland, OR. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.