Vermont is not a state noted for sun. In fact, sunshine-wise, we’re nearly the gloomiest state in the nation, second only to dank and lightless Washington, where apparently nobody in Seattle ever leaves home without an umbrella.

Tucson, Arizona, gets 193 sunny days each year; Albuquerque, New Mexico, gets 167; and San Diego, California, gets 146. Vermont gets a measly 58. No wonder New Englanders have a reputation for being dour.

Sun is an issue for gardeners, since so many plants need such a lot of it. Tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, peas, beans, corn, and squash all do best in conditions of full sun, which is officially defined as at least six hours of direct sunlight per day. Even the leafy bits of carrots, radishes, and beets need at least a daily half-day of sun. Spinach, kale, and lettuce, my gardening manual says, are tolerant of shade, though even so they don’t thrive in caves or under the porch. We need that sunshine.

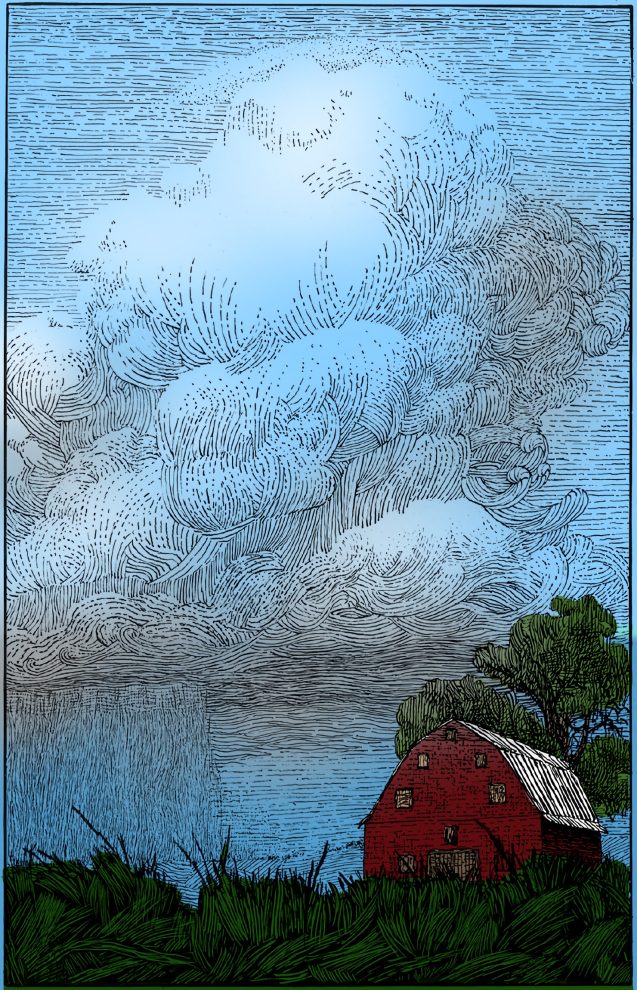

Some people, on the other hand, positively rave about clouds. The Cloud Appreciation Society—founded in 2005 by cloud aficionado Gavin Pretor-Pinney—is a band of 15,000 or so cloud-lovers worldwide, all dedicated to defending, describing, admiring, watching, and photographing clouds. The Society’s multi-point Cloud Manifesto points out that not only are all-blue skies blah and monotonous, but that clouds are important indicators of atmospheric moods and that contemplation of shapes in them profits the soul and therefore saves observers money that might otherwise be spent on exorbitant psychiatric bills.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Christina Rossetti, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Emily Dickinson all wrote poems about clouds. So did A.A. Milne, for Winnie-the-Pooh, who was pretending to be one while dangling from a blue balloon. Descartes wrote a philosophical essay about clouds. John Constable painted them. Claude Debussy wrote a cloud nocturne, and Joni Mitchell and the Rolling Stones sang cloud songs.

And scientists take clouds very seriously.

Just for starts, clouds are complicated. There are at least ten different types of clouds, divided into genera and species, all with Latinate names—this last the brainchild of Luke Howard, a British pharmacist, who in 1803 wowed scientific circles with his “Essay on the Modifications of Clouds.” It was Howard who gave us such wordy cloud mouthfuls as cumulonimbus and stratocumulus lenticularis, all more precise definitions of what people had previously described as puffy and curly, or flat and depressing.

Clouds of various kinds, at any given moment, cover about two-thirds of our planet. The Earth, spied on from space, is a fat blue ball, liberally splattered with white—and it turns out that all those white swirls, curls, and blobs play an essential role in regulating the Earth’s climate. We know this because recent computer simulations have some ominous things to say about what happens when clouds go away.

Clouds, as all of us learned in elementary school via those ready-to-color diagrams of the water cycle, form when sun-warmed water evaporates from the Earth’s surface—to the tune of 285 cubic miles a day from the world’s oceans, a total of 300 trillion gallons heading upward every 24 hours. In the upper atmosphere this water vapor cools and condenses around particles of dust, salt, pollen, or other teeny stuff to form cloud droplets, of which there are over 100 million in every cubic yard of cloud. Planetary quirks of temperature, turbulence, wind, radiation, and geography all affect this process, which is why clouds and climate—even for a supercomputer—are tough nuts to crack.

The newest computer models, however, all show bad news for clouds. Clouds play a major role in cooling the Earth, intercepting incoming sunlight and reflecting it back into outer space. Perversely, however, as the Earth warms, clouds, like shrinking puddles, begin to disappear.

Physicists at the California Institute of Technology took a particular look at stratocumulus clouds—the low-lying, blankety kind that have by far the largest cooling effect on the planet. In their computer simulations, they found that when the carbon dioxide level in the air hit 1200 parts per million—a number that persistent fossil-fuel burning could well bring us to within the next century—the clouds disappeared altogether. The result? Relentlessly blue skies, an estimated 8oC (14oF) leap in planetary temperature, equatorial oceans as hot as hot tubs, and wholesale economic collapse.

It’s clear we need those clouds.

While this should concern all of us, there’s no need yet to throw down our hoes and trowels in despair. We’ve got a long way to go to the fatal 1200 ppm tipping point. (Carbon dioxide levels now are just over 410 ppm—up from 280 ppm in the days prior to the Industrial Revolution.) There’s a lot we can do before reaching the point of no return. There’s even a proposal—a suggested joint project between American and Chinese scientists—that, if push comes to shove, we might create artificial clouds by injecting aerosols into the upper atmosphere, a process proponents refer to as solar geo-engineering.

I’ve got to say, though, that I don’t want fake geo-engineered clouds. I want to save the clouds we’ve got. And in view of all this, I find I’ve stopped whining about Vermont’s periodically unsparkly skies. I appreciate

clouds.

Because—yes—all our tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, peas, beans, corn, and squash need sunshine.

But they also need rain. ❖

This article was published originally in 2019, in GreenPrints Issue #118.