Do you own a Christmas cactus; or Schlumbergera bridgesii? I’ve always liked the look of them, with their reaching little green fingers and funky pink blooms at the tips, but I never knew much about them until this year, which inspired me to purchase one myself. I like a challenge, I guess.

For example, did you know that this species is actually a succulent, not a cactus? It’s true! Despite its common name, the Christmas cactus is an epiphyte native to Brazil. Its leaves are made up of segmented pads that store water like many other succulents, and its stems tend to be quite thin and wiry. To be honest, had I known it was a succulent, I would have avoided it. Those buggers just don’t appreciate all the love I want to give them!

For a Christmas cactus to bloom, it needs to be exposed to cooler temperatures and shorter days. Some people even put them in closets for the weeks leading up to Christmas, which is when it really does tend to bloom. Unlike a cactus, you can’t just leave them to dry out for months on end, but they do only need light watering about once a month. I, of course, only say this based on what my gardening friends have told me, but so far mine has survived the holidays, just like the rest of us!

In today’s story, What’s in a Name? Diana Wells tells the story of a house fire, and the lone plant that survived as well.

Enjoy More Gardening History

This story comes from our archive that spans over 30 years, and includes more than 130 magazine issues of GreenPrints. Pieces like these that turn gardening history into everyday life lessons always brighten up my day, and I hope this story does for you as well. Enjoy!

What’s in a Name?

Sometimes very little, indeed. Other times…

By Diana Wells

By the time you read this, we will (God willing) be back in our house, after over nine months (nine months!) in a hotel while damages from a house fire were being repaired.

In many ways I’ll be sorry to leave our room at 110 Pheasant Run. I love the people here—they’ve become like family. Our towels are picked up and many of our meals are provided. The dog loves everybody and even seems to enjoy walks around the—to me—sterile landscape that surrounds us. Of course she can smell things I cannot see. All I notice is the monoculture grass with absolutely no weeds and the plants pushing out of piles of dyed black mulch. There are some birds, yes, but if ever there was a pheasant running around here, it must’ve been long ago.

Odd, isn’t it, our nostalgic tendency to name places after what is no longer there. I can remember a magnificent buttonwood, or sycamore, tree not far from us. It must have been hundreds of years old. One day when I passed, it had been felled and where it had reigned, a raw pond was being dug. Next to the pond was a gilt-edged sign announcing “Buttonwood Farms,” a new, very fancy residential development (farming what exactly?). I wrote to the local paper asking if all nature around us was to be replaced by golden signs and learned that the developer—to give him credit—promised to plant new buttonwoods around the pond. That was years ago. Those buttonwoods have grown somewhat, and children fish in the pond. But the trees are still nowhere near the venerable giant they replaced—a tree that happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, even though it was here generations before our much-espoused “progress.”

Pheasant Run surrounds the industrial development where our hotel is situated. When first I came to the USA in the 1970s, there were still pheasants around. So perhaps there may still have been the odd one or two running here when the road was made. They’d be massacred immediately by cars and trucks if they were here now. In fact, there aren’t many pheasants around here any longer—even in the country—probably because foxes, once seldom seen, have become common. Actually, pheasants aren’t native to America but came from Phasis in (Eurasian) Georgia. Henry VIII first reared them in Britain, replacing falconry with game-chasing (as pheasants are too heavy for hunting birds to carry).

Other nature-named places around us include “Swan Place,” which isn’t even near water, and “Fawn Hollow,” which doesn’t need to be nostalgic: There is no shortage of deer here in Bucks County, PA, the leading area for Lyme disease in the country.

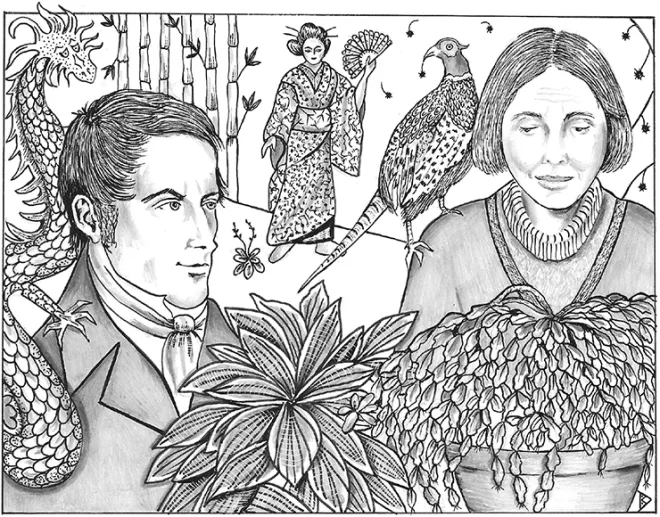

Names and their memories are too big a subject to explore much here, but they are certainly common in the plant world. I often think about Philippe von Siebold, a German doctor who explored Japan in the early 19th century. At the time, Japan jealously guarded its natural resources from foreigners, allowing botanists to live only on a man-made island called Deshima in the harbor of Nagasaki. Only Dutch botanists were allowed, but Siebold, who spoke Dutch, explained his heavy German accent by saying he came from a remote village in Holland (did the Japanese authorities possibly picture a mountain village in this below-sea-level country?).

I’ve reached an age when many of my contemporaries are having cataract surgery, and I love to tell them how Siebold managed to travel through mainland Japan removing cataracts—yes, in the 19th century—and taking native plants as payment. It was he who introduced hostas to Europe, and, indeed, some carry his name. So cataract-surgery gardeners who grow hostas have a double reason for remembering this forgotten man. I suppose such gardener-patients could offer their surgeons rare plants as payment?

So many forgotten persons are commemorated in the names of plants. When I return home, I’ll find my Christmas cactus on the porch where it was shoved when the house was cleared for restoration. Its botanical name is Schlumbergera bridgesii, after two nineteenth-century botanists who explored South America. In spite of the “free Internet” offered by our lovely hotel, I have been able to discover very little about these men (how I miss my home library!), only that Thomas Bridges brought seed of the huge Amazon water lily to Europe and that he probably died of typhoid fever.

But it’s not a bad legacy to live only in a Christmas flower. I think my Christmas cactus will bloom this year in spite of its smoky experience. It’s about the only houseplant that survived the fire, and when it blooms it will, for me, be a symbol of endurance, of hope and rebirth.

A joyous part of Christmas. ❖

By Diana Wells, published originally in 2017-18, in GreenPrints Issue #112. Illustrated by Blanche Derby

Does this story remind you of one of your own? Do you have any fun Christmas cactus stories? Leave a comment and share it with us!

I received a Christmas cactus cutting from some dear friends when my 3rd son was almost two years old. Through the years it grew and bloomed crimson each year. I repotted it into an “ancient archeological pot” that I made in a ceramics class, and it flourished! Somehow it acquired the name ‘Herman’ and he thrived through all of the high & low temperature fluctuations, moves and jostling of 5 boys. When I was mobilized for active duty with the Navy Reserve, Herman was cared for by my friend, then by her parents. Herman is almost 40 yrs old now and still blooms on my friends parents porch. He is well cared for and loved.