There’s a lot of “science” from 2,000 years ago that we can safely ignore. Sure, we might look back and realize how far we as humans have come. And we might thank our lucky stars that we no longer view things like solar eclipses as a reason to hide from angry gods. I know I’m happy that leeches aren’t the common medical cure-all that they once were!

Other science, however, especially some gardening science, has stood the test of time. We know crop rotation works as a way to help limit disease and give our soil time to recover. We know a healthy ecosystem with bees, beetles, butterflies, and birds is good for a garden. Writer David A. Bainbridge also appreciates one particular bit of ancient gardening science.

In his story, That Good Old (Very, Very Old) Garden Advice: Over 2,000 years old!, he shares what he learned from Fan Shengzhi, a Chinese agronomist who produced what is believed to be the first scientific agricultural manual in China. David also reports that Shengzhi’s work is “considerably more sophisticated than contemporary Greek and Roman works.”

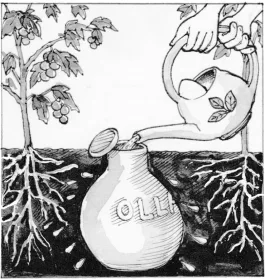

Specifically, David explores Shengzhi’s description of clay pot irrigation systems, and how surprisingly well they work. Even with all of our technology and advanced irrigation systems, this simple, low-tech idea from more than 2,000 years ago can stand the rigors of good old gardening science. Plus, it gives us an excuse to go dig into the earth, and that’s always a good idea.

Get More Stories About Gardening Science

This story comes from our archive that spans over 30 years and includes more than 130 magazine issues of GreenPrints. Pieces like these that inject gardening science into everyday life lessons always brighten up my day, and I hope it does for you as well. Enjoy!

That Good Old (Very, Very Old) Garden Advice

Over 2,000 years old!

By David A. Bainbridge

As an author, I often wonder what impact my years of research and writing will have. My wife has observed that it seems to take about 30 years for the world to see what I see. In 1986, for example, I started writing about building with straw bales—and this year straw bale construction is in the International Building Code.

But hey, just 30 years—what have I got to com-plain about?

Consider Fan Shengzhi, a remarkable Chinese agronomist from over 2,000 years ago. In about 10 B.C., Emperor Chengdi sent Fan Shengzhi to Sanfu to learn how to improve yields for resource-limited farmers. Fan had practical experience in agriculture, was honored as a master teacher, and was a skilled observer, interviewer, and researcher. He traveled extensively talking to farmers. After gathering all his information, he prepared a manual on high-yield agriculture, with information on plowing, sowing, soils, fertilizer, grafting techniques, crop rotation, intercropping, multiple cropping, mixed cropping, buried clay pot irrigation, and fermentation for food storage. The book he assembled was probably the first complete scientific agricultural monograph in Chinese history—and considerably more sophisticated than contemporary Greek and Roman works.

Sadly, only fragments remain, but it is still useful today.

Fan’s approach was very scientific, discussing expected planting and harvest rates. He cited wheat yields of 1,000 pounds per acre. The U.S. did not reach comparable wheat yields until 1906, and consistent yields this high until the 1940s.

But the section of Shengzhi’s manual that captured my attention the most was his description of buried clay pot irrigation:

Make 210 pits per acre, each pit 24 inches across and 6 inches deep. To each pit add 38 pounds of composted manure. Mix it well with an equal amount of earth.

Bury an earthen jar of 1.5 gallons capacity [such as the GrowOya or Dripping Springs ollas] in the center of the pit. Let its mouth be level with the ground. Fill the jar with water. Plant four melon seeds around the jar. Cover the jar with a tile. Fill the jar to the brink when the water level falls.

At the time, I was working on desert restoration and dryland agriculture for the Drylands Research Institute at the University of California, Riverside. Intrigued, I soon had buried clay pots in the garden with a variety of crops. They worked even better than I expected. The slow flow of water through the clay walls is influenced by water use of the crop—becoming a very efficient demand-response system. I later went on to do much more extensive research with the pots and have never failed to be impressed. Thank you, Fan Shengzhi!

So, to my fellow authors, have hope! Perhaps 1,000 years from now someone will uncover an ancient GREENPRINTS, find a fragment of your story—and it will change their lives and help others around the world! ❖

By David A. Bainbridge, published originally in 2016, in GreenPrints Issue #106. Illustrated by Linda Cook Devona

What are some of your favorite gardening science facts or discoveries? Share your thoughts in the comments!